The discovery of business papers and daybooks, dating from 1833 to 1844, shed light on an unexpected character. Anthony Carter was a freed Black businessman of Lewisburg. We know Anthony as a husband, a father, a cobbler, and a landowner through studying his papers and Greenbrier County court records. These resources allow a rare glimpse into a freed working-class Black family’s determination to thrive in a slaveholding society.

WORKING & WASHING

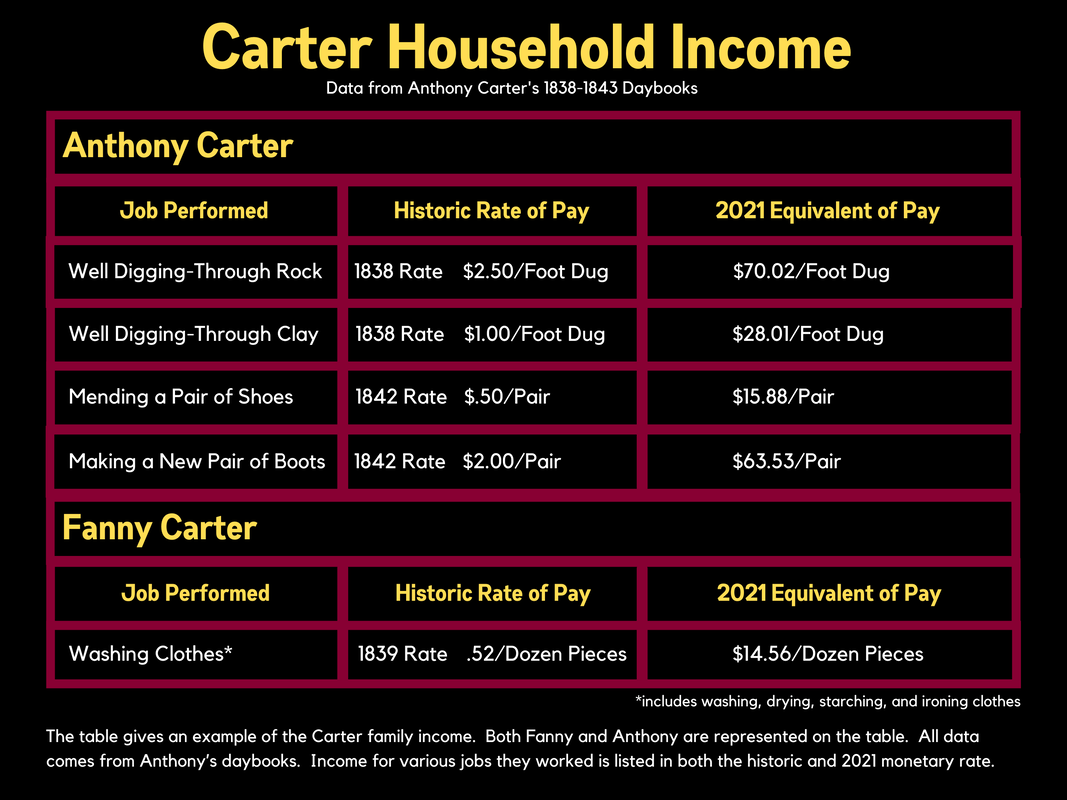

Anthony Carter, his wife Fanny, and their three children were owned by Henry Erskine until July of 1837. It is unknown why Erskine emancipated the Carter family when Anthony and Fanny were still valuable property at ages forty and thirty-seven. Two years after emancipation, Anthony learned a new trade, cobbling. Cobblers were essential in nineteenth-century society because shoes needed regular mending. Anthony rented basement space beneath various shops downtown. He began to cobble for some of Lewisburg’s most prominent families and their enslaved people, including Star Hotel owner, James Frazer.

Fanny contributed to the household as a laundress, at times making more money than Anthony. She spent long days tending and boiling the wash, using harsh lye soap, starching and ironing clothing. Anthony’s daybooks recorded how many dozens of pieces of laundry Fanny was doing and how much money he would be paid for her efforts.

Fanny contributed to the household as a laundress, at times making more money than Anthony. She spent long days tending and boiling the wash, using harsh lye soap, starching and ironing clothing. Anthony’s daybooks recorded how many dozens of pieces of laundry Fanny was doing and how much money he would be paid for her efforts.

STRUGGLING & SUCCEEDING

Less than a year after emancipation, Anthony was summoned before the court to defend his family’s right to remain in the county. Since 1806, Virginia law mandated that any freed Black person was required to leave the state unless granted special permission. Even with approval to stay, Anthony was brought before the court multiple times between 1838 and 1842. Despite this harassment, he continued to work and make payments to purchase an acre of land just east of Lewisburg for his homestead.

The end of Anthony’s life was encompassed by misfortune as he faced bad health, debt, personal demons, and possible estrangement from his family. After Anthony’s death in 1844, Fanny continued to live locally according to the 1860 Census.

Anthony’s business papers are important because they highlight the day-to-day life of a freed Black family. Anthony and Fanny Carter’s fierce determination presented an alternative to a community burdened by enslavement.

The end of Anthony’s life was encompassed by misfortune as he faced bad health, debt, personal demons, and possible estrangement from his family. After Anthony’s death in 1844, Fanny continued to live locally according to the 1860 Census.

Anthony’s business papers are important because they highlight the day-to-day life of a freed Black family. Anthony and Fanny Carter’s fierce determination presented an alternative to a community burdened by enslavement.