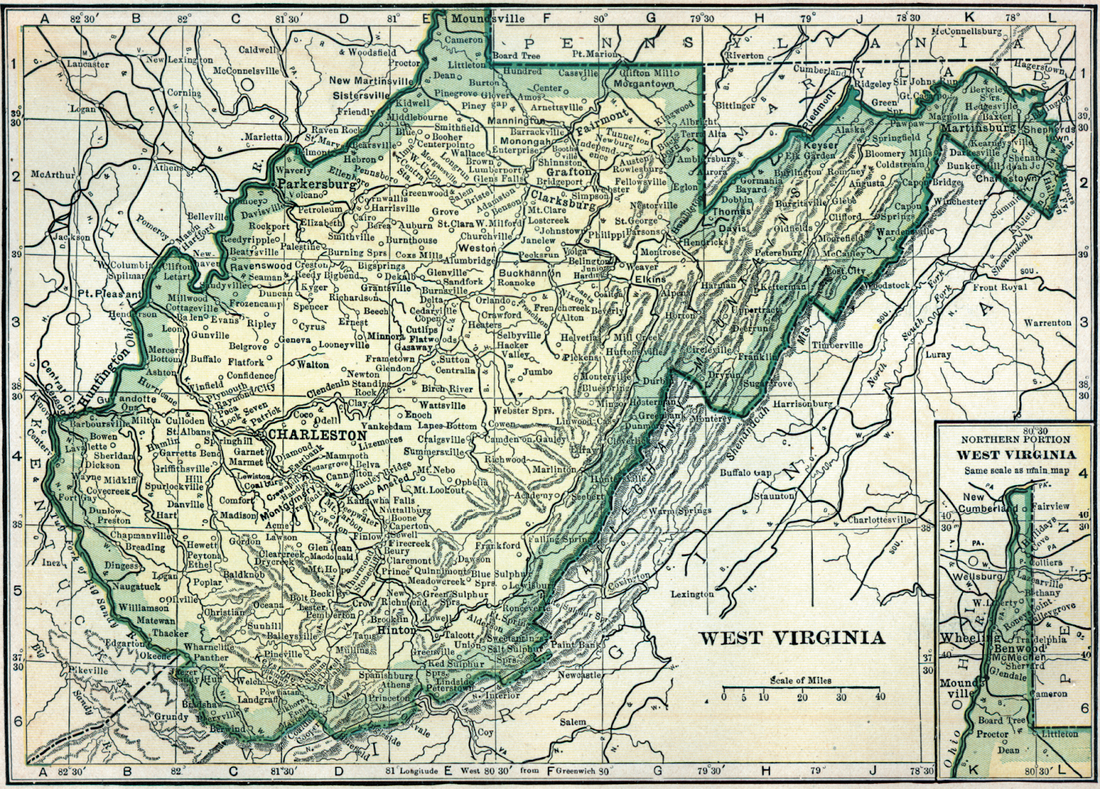

MOTHERS OF MATERIAL IN GREENBRIER COUNTY

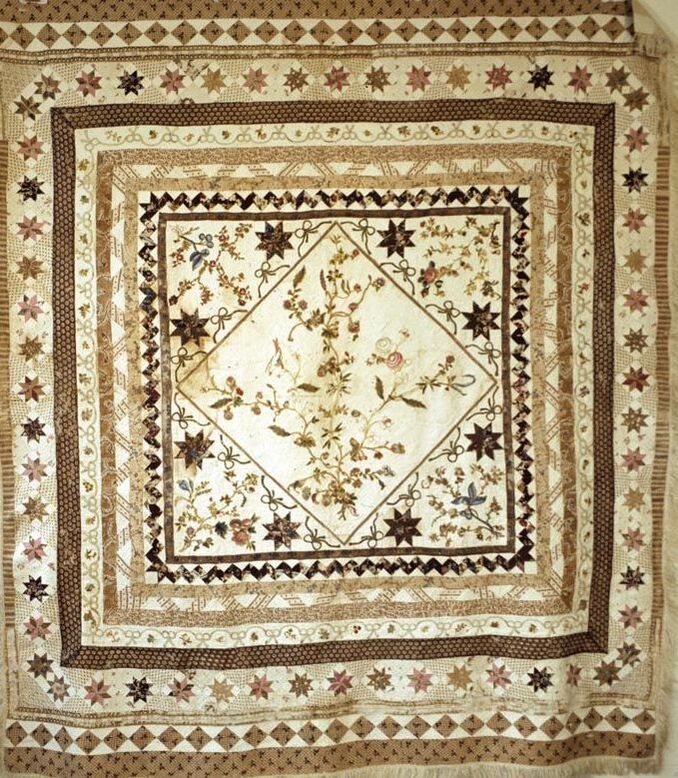

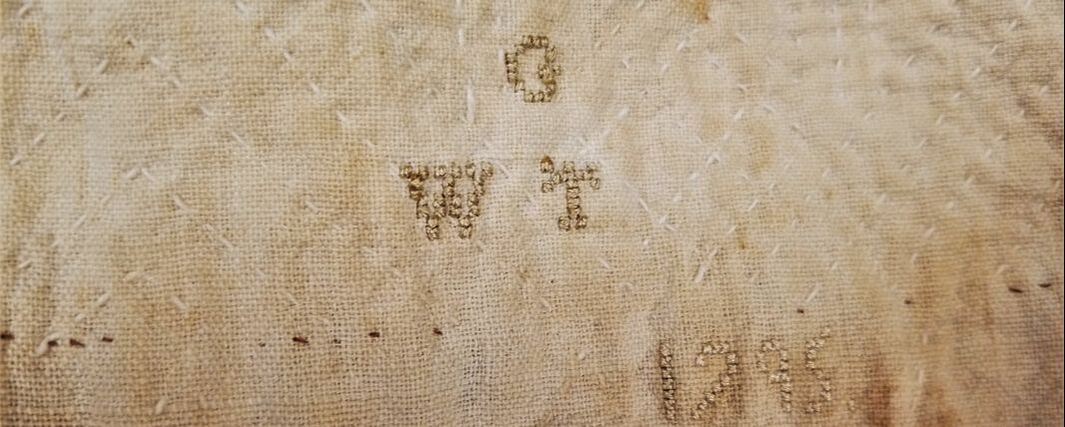

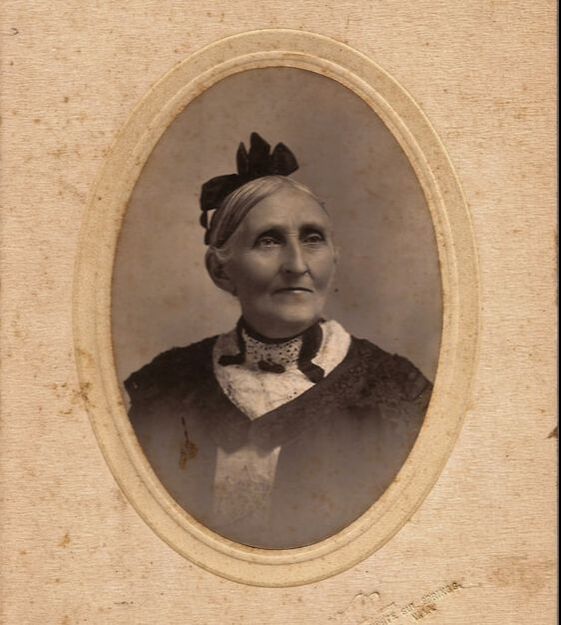

Textiles are woven into every aspect of our lives, from the clothes we wear to our bedding, carpets, and towels. Humans depend on their warmth and comfort as well as their use in decorative self-expression. Women were an important part of textile manufacturing, both at home and commercially in the Greenbrier Valley of West Virginia. These women’s stories and processes are revealed through their creations.

Each innovation in textile production made things easier for women by changing their access to materials and tools while allowing for growing creativity. Today we still value the art of historic textile production and can appreciate the hardships faced by women who raised their families, tended the home, and helped with the farm while still producing these beautiful textiles.

Each innovation in textile production made things easier for women by changing their access to materials and tools while allowing for growing creativity. Today we still value the art of historic textile production and can appreciate the hardships faced by women who raised their families, tended the home, and helped with the farm while still producing these beautiful textiles.

|

This project is presented with financial assistance from the West Virginia Humanities Council, a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations do not necessarily represent those of the West Virginia Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

|