|

https://wvhistoryonview.org/catalog/007330

From the mid 1880s to the late 1920s, Lewisburg, West Virginia was a massive producer of turkeys, and at one time was even considered the turkey capital of West Virginia. Lewisburg was well known for their “Great Turkey Runs,” when they would drive hundreds of birds down Main Street in downtown Lewisburg. The turkeys were gathered from local farms; there were no large corporations. These turkeys would be driven through Lewisburg and down to Ronceverte, where they would then be put on a train and shipped out. Turkey production plummeted in the late 1920s due to the Depression, World War II in later years, and the decline of railroad dominance. Lewisburg is no longer the turkey capital of West Virginia, but it still holds a prominent role in turkey production. British United Turkeys of America (BUTA) came to Lewisburg in the mid 1980s, but were bought out by Aviagen Turkeys in 2005. Aviagen Turkeys, is one of the most prominent and well respected suppliers of breeding stock worldwide. Aviagen currently has more than 8,000 employees, serving in 100 countries, including a livestock breeder right here in Lewisburg. Will Lewisburg ever regain their title as the turkey capital of West Virginia?

0 Comments

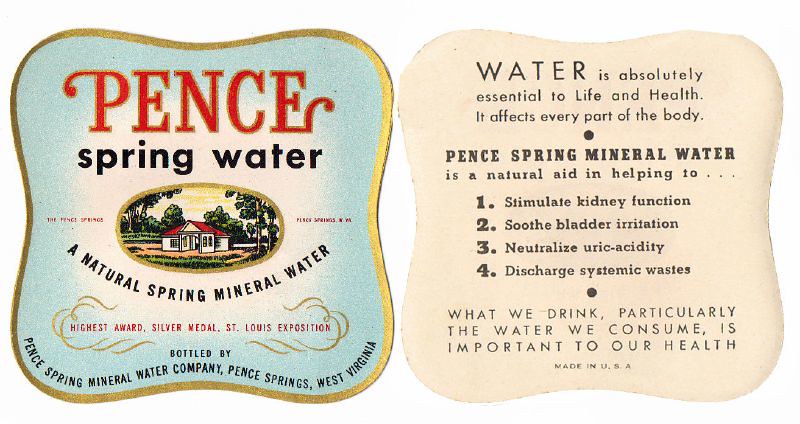

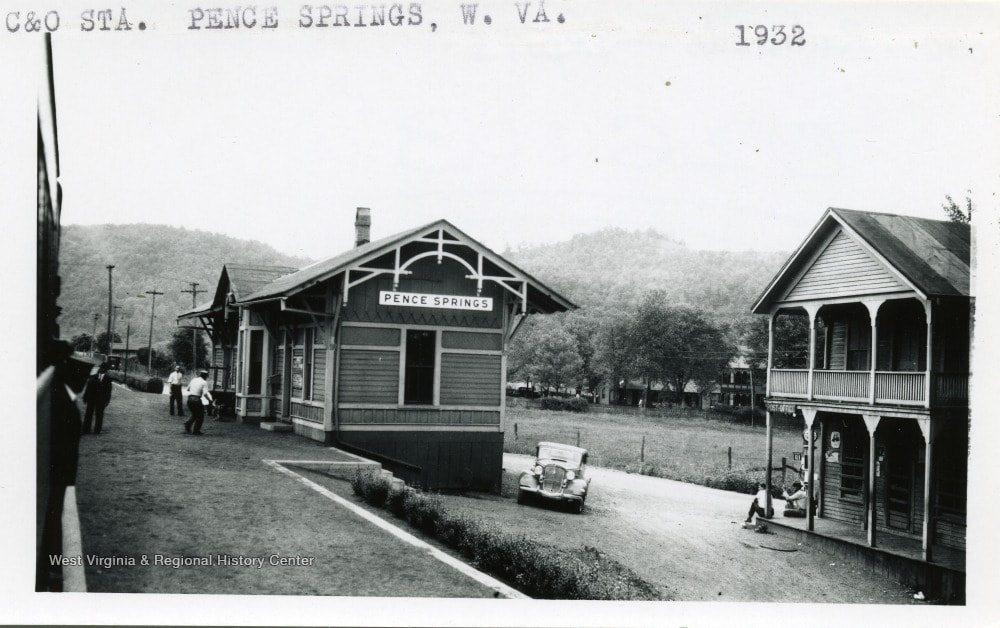

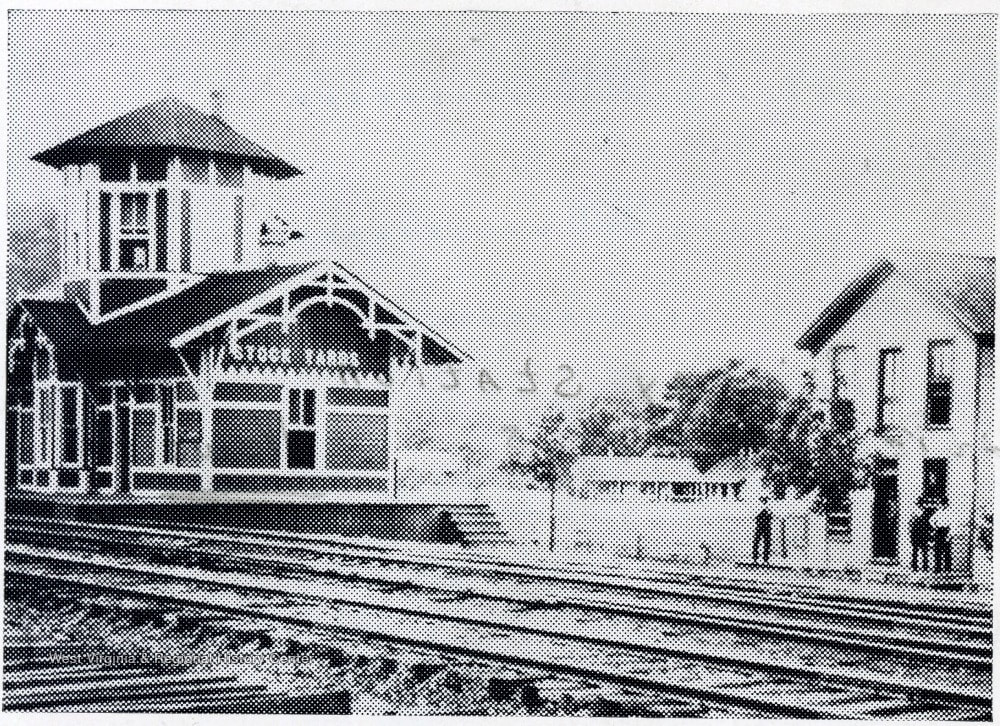

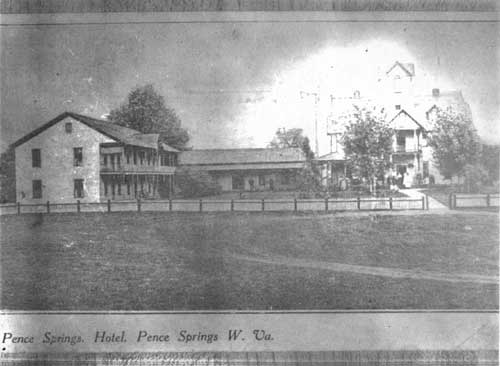

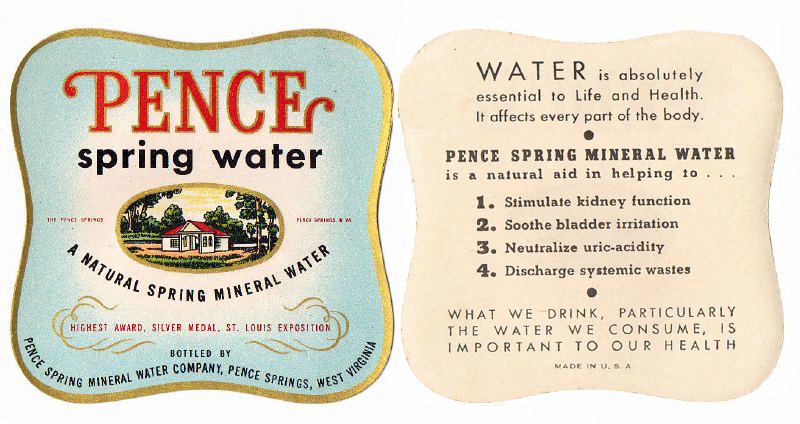

Pence Springs in Summers Co, WV is named so due to the spring resort established by Andrew Pence. Andrew used the natural spring water for his resort guests to drink (at this time spring water was believed to have healing properties) and in 1882 he started bottling the water from the spring to sell. The water became famous across the county when it won a silver medal for its “high quality of the spring sulpho-alkaline” at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904. In the 1890’s the first hotel was built, but would burn down in 1912. Horse drawn carriages would bring guests from the local stockyard/ train station to the hotel. The second Pence Springs Hotel was built in 1918 conveniently built on the hill above the spring to let guests easily spend the night and enjoy the healing waters.

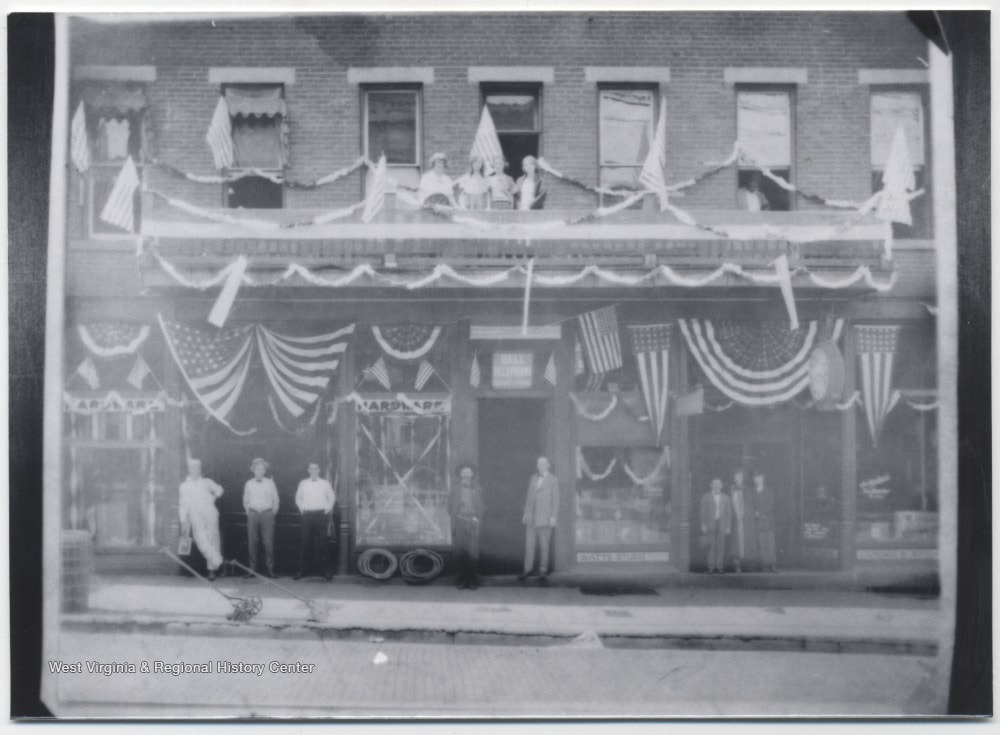

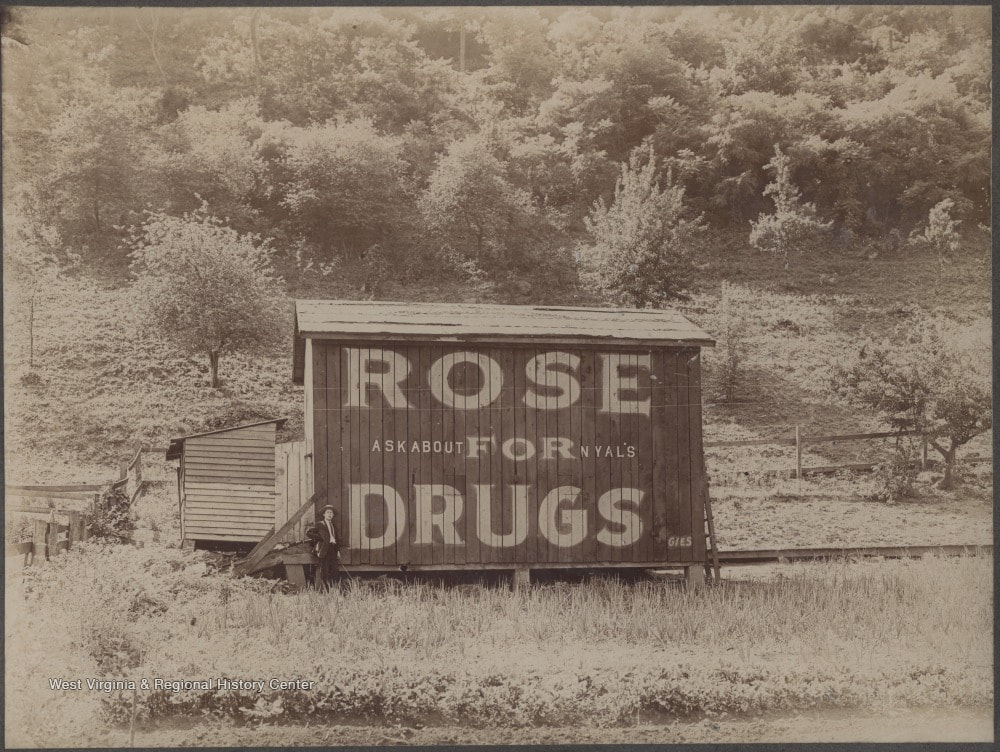

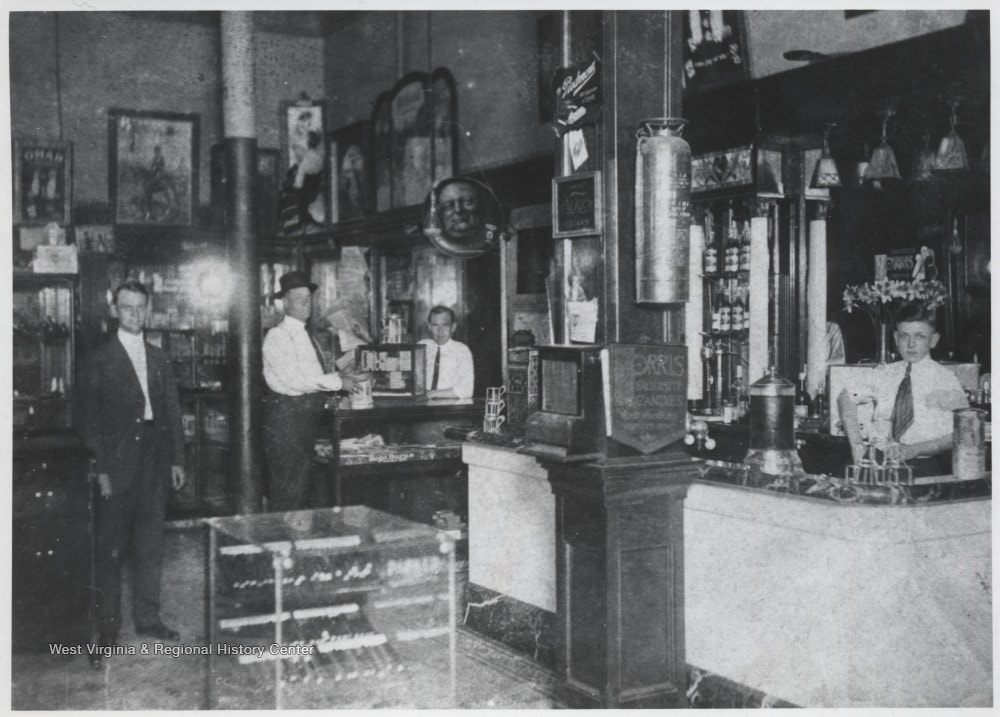

During the “Roaring '20s” the building had some hidden secrets. While most guests came to “take the waters,” others came for the hidden bar in the basement that acted as a speakeasy during prohibition. Any visitor coming to the bar had the option to come from the train station in a window-tinted limousine so as not to be seen. The illegal alcohol was imported from Kentucky until the hotel started their own whiskey distillery. The hotel also bought moonshine from the locals of Summers Co. In the 1920s, guests could also enjoy the golf course, pavilion ballroom, and casino. Gambling and illegal alcohol made the hotel a classic roaring '20s party, but it all had to be “hush hush.” In 1913, West Virginia was under the Yost Law to enforce prohibition. By 1920, prohibition went national with the Volstead Act. Sheriffs, constables, city police, and eventually the state police would all enforce the dry law by hunting down bootleggers and moonshiners. If you're looking for a legal good time with all the same thrills that the 1920s had to offer, come join the Historical Society’s 1920s party/fundraiser at Stellar Evening, December 3rd at 6:30pm, in the gymnasium of the Greenbrier Community School. Wear your best 1920s attire and get ready to dance! Tickets are on sale now! Get them while you can, as seats are limited. Tickets will only be sold until December 1st, 2022. There will be NO ticket sales at the door at the time of the event. Admission is $50 per person, or you can choose to sponsor a table for 4 or 8 people. Hope to see you there! www.eventbrite.com/e/stellar-evening-2022-tickets-460279998867 For several months now the Hinton community has been anticipating the opening of a new department store, called Roses. The old Magic Mart building in Avis had been shut down and empty until Roses started moving in and hiring staff this year. With an opening date in early November, the town has been waiting to see what this new store might be like. What some might not know is that Hinton has seen a Roses before, but under different management; and it was 100 years ago, literally. The Roses coming to Hinton in November 2022 is a discount store that was first founded in Henderson, North Carolina in 1915 by Paul Howard Rose. Roses was bought by Variety Wholesalers Inc. in 1997. Back in the early 1900s, Shan Rose of Hinton founded and ran the Rose’s Drug Store in downtown Hinton. It was located at the corner of 3rd and Temple. In the heyday of the Roses Drug Store there were advertisements all around town using their slogan “Get it at Roses”. These advertisements were on their trucks (which offered free deliveries, no matter how small) and on the side of barns. They even had a float in the WWI Victory Parade and decked out the store to celebrate the end of the war. The Rose family owned and managed the store. In the image below you can see founder Shan Rose, his son John Rose is behind the counter, and his son Charlie Rose is working as the fountain boy. Founder Shan Rose is pictured here with his dog. The family is buried at Hilltop Cemetery in Hinton, WV.

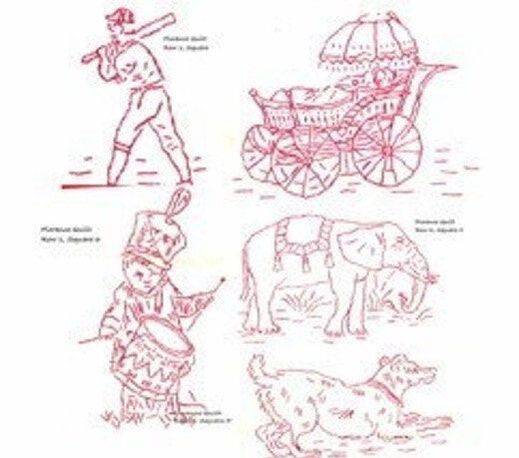

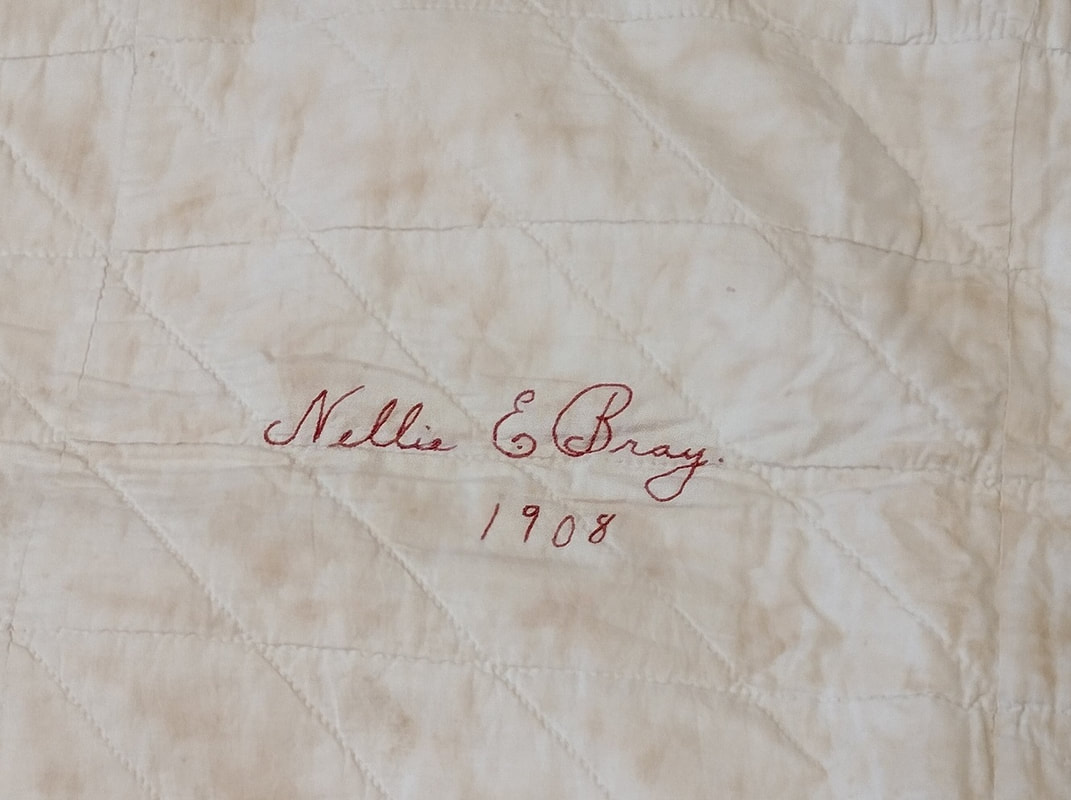

On 19th century American farmsteads, comfort in the form of food and textiles were expected to be provided by the woman of the house. Soft, warm furnishings were made in the home or done without. Little girls in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries worked samplers where they could practice alphabet and numbers while gaining facility with needle and thread. Most of us have seen examples of these; considered antiques, they are collected. Somewhat less well known, quilting was another needle art that introduced young girls to necessary homely skills that could be decorative as well as useful. Making warm quilts for a growing family was an expected task, just as weaving coverlets had been before inexpensive cloth became widely available and looms were put away. We have a couple of these little textiles out on display in the dining room of the North House Museum as part of our celebration of National Quilt Month in March (and into April). Their makers were probably stitching with their dolls in mind. Jane Hughes, retired librarian and long-time volunteer in the Greenbrier Historical Society’s archives, shared with us a quilt her grandmother made as a girl of 10. Known as Redwork, these white quilts with red embroidered animals, plants and people were popular in the late 1800s - early 1900s, and pattern books could be purchased. The actual quilting was as important as the embroidery, though many examples of unquilted tops exist. The quilting was less fun than making embroidered pictures. If you look closely at Nellie’s quilting, you can’t help but be impressed with her neat lines, her ability to achieve 10 to 12 stitches to the inch, and the perseverance required to complete the quilt. We don’t know the identity of the girls who created the doll-sized quilt tops in our collection, but we do know about Nellie of the Redwork quilt, not the least because she signed and dated her work. If only every one of our quiltmakers had done that! Born in 1888 to a family in the Midwest, Nellie Edith Bray Becker grew up to be a no nonsense, practical farm wife. She made handsome quilts for her family but maintained that beauty was beside the point of a quilt; and yet, this her first quilt, a sampler finished in 1908, shows a definite penchant for decorative work and awesome stitching.

More Than A School – Collective Memories from Bolling School Alumni -- By Arabeth Balasko “A forgotten past is a past that is yet to be. A forgotten history is a memory missing from our collective conscience. An incomplete history is like an incomplete mind that has forgotten who it is and where it came from.” ― A.E. Samaan What do you remember about your early school experiences? Can you recall the exact details of your classroom’s layout? What about the smells of the hallway? Do you remember all of your teacher’s names? What about significant moments in time – do you remember where you were when you found out about these life-changing events? In December 2021, I had the privilege to speak with two alumni from Bolling School, a former segregated school located in Lewisburg, West Virginia. Bolling School operated as both an elementary and high school and became the only high school open to Black students in Greenbrier County prior to desegregation. Although it officially closed its doors as a segregated institution in 1964, Bolling School’s legacy has lived on in its alumni for decades. Today the school’s layout has changed physically, but in the memories of Mr. Alex Pryor and Mr. Marion Gordon, Bolling School looks just as it did in the 1950s. Both now in their 70s, each can still recall every detail of their time at Bolling School. Their stories, although different, shared many collective notes – the influence of their educators, the compassion and care of their community, and their lifelong connection to, and their love for the Bolling School transported me back in time with them as they shared their memories with me. Their interpretation of growing up during the Civil Rights Movement in Greenbrier County, West Virginia and their personal experiences of racism and discrimination juxtaposition with their stories of individual successes and triumphs. These unique and shared experiences serve as gateways into the past – memories and stories allow for individuals to connect with one another on a deeper, more meaningful level. Oftentimes, we as people shy away from hard histories, hard conversations – we can minimize hurts, and maximize virtues, but I feel that is a misstep. History is ugly, sad, beautiful, heartwarming, heartbreaking, and real. It happened. We cannot change that, but we can work together to showcase how it happened, why it happened, and help reshape it for today’s generation through a modernized lens. It is one way to step forward into a new story, a new era of oral histories and shared experiences. By encouraging folks to use their voices, to speak their story, and share their truth, there is a lot of healing and rebuilding which can happen in the humanities realm. I will close with this – I feel that it is always important to stay human – meaning, approach all you do with an open-mind, an inquisitive nature, and a listening ear. You never know how your approach, your efforts, your “expressions of love,” can repair a damaged relationship, inspire a new generation of folks, or encourage others to take ownership of their stories and reclaim their voices. To hear Mr. Pryor and Mr. Gordon's Oral History interviews about their time at the Bolling School, please click on the videos below to be redirected to the Greenbrier Historical Society's YouTube channel!

AND if you, or someone you know went to Bolling School and would like to share your/their story with us, please reach out to us at 304-645-3398 to learn more!

|

SOCIAL |

PHONE |

ADDRESS |

814 WASHINGTON ST W

LEWISBURG, WV 24901 |

Experiencing issues with this page? Email [email protected].

RSS Feed

RSS Feed