|

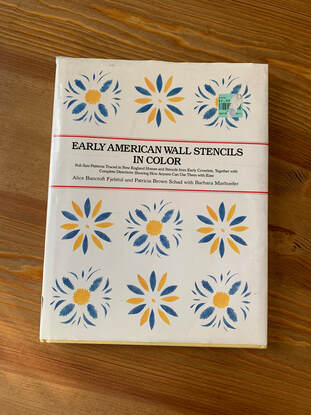

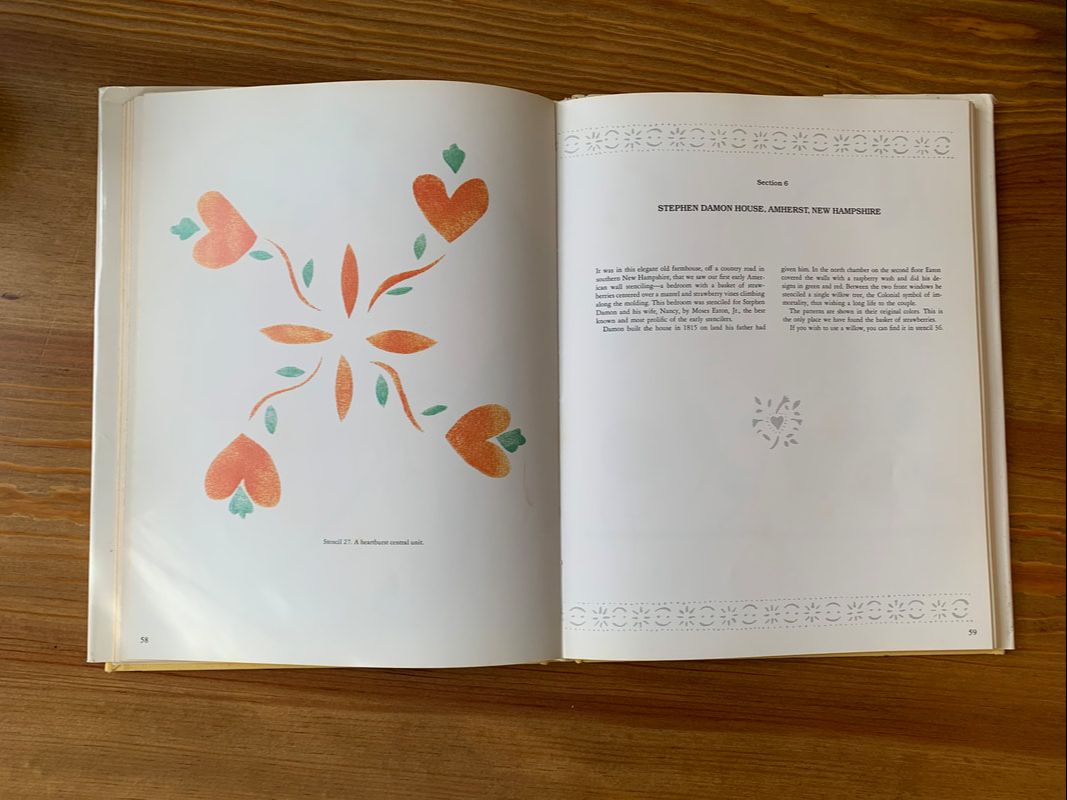

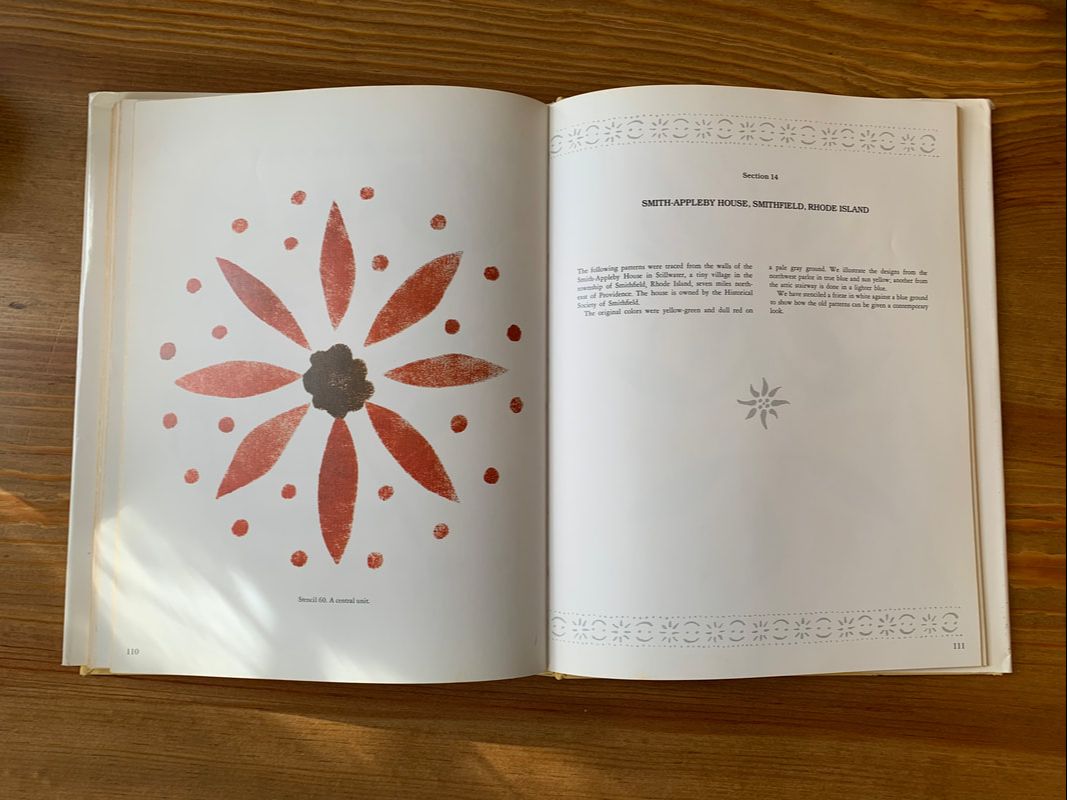

Come Learn About Historic Tavern Stenciling with Deb Marquis-Cascio -- By Arabeth Balasko When Deb, the Greenbrier Historical Society's Lead Docent and Museum Associate, began an intensive stenciling project in July 2021 at the North House Museum, she embarked on a journey that would transform our historic space into a working tavern room! This stenciling project has been a true "labor of love," for the Greenbrier Historical Society team. The newly configured area has become a mode of "transport," which has enabled patrons to step back into time and visit the Frazer's Star Hotel Tavern Room, which was a popular establishment in Lewisburg, West Virginia during the 1830s-1850s. In 1836, James Frazer purchased the North House. He immediately began to renovate and expand the property's footprint, and turned the once familial dwelling into the Frazer's Star Hotel and Tavern. During these renovations, Frazer added two additional wings of rooms for guests and other various outbuildings. Recently, the North House Museum team found an 1854 description of the property under Frazer's ownership, which stated, "...there are two good cellars, an orchard, a vegetable garden, a fifty-horse stable, outhouses comprising of servants’ (enslaved) cabins, kitchens, a meat house, and a dairy." The Frazer Star Hotel and Tavern operated until Frazer’s death in 1854. Thanks to the hard work of the North House Museum team, the newly renovated Tavern Room now serves as both an educational period room and an event space. During their visit, visitor's can learn about the history of the Frazer family, the enslaved presence at the Star Hotel, and the role of hotels and resorts during the mid-1800s. To learn more about the most eye-catching addition to the Tavern Room, the period-accurate historic stenciling, check out the interview below between Greenbrier Historical Society AmeriCorps Member, Arabeth, and our skilled stencil artist, Deb. Q. What drew you to pick those specific color schemes and patterns for the Tavern Room stenciling project, Deb? A. "Well, the okra color for the walls was already picked out from historic paint samples -- our goal was to make it as authentic and historic to the time period as possible. I ended up doing a lot of research on 19th century Tavern Rooms because we did not have any real pictures of what the Tavern Room here looked like at that time -- but even if we had, they would have been in black and white anyway. Ironically, I kept seeing the okra colored walls in my research, and it was really kind of serendipitous that we had already chosen that color for the walls! The colors I saw used the most were the reds, rusts, greens, and okras. We decided that if we stuck to just a few colors in our scheme, we could put as many patterns up as we wanted to in the room -- and it would all go together, it would all be cohesive! I choose the pineapple since it symbolized a sign of welcome. It would often go over doorways and in public places. The other stencils I choose were pretty typical to the day, they didn't necessarily have a specific meaning. The bird was chosen because it is going to be an overall theme of the room -- both above the mantel and incorporated into the fabric for the curtains. The other stencils were just 1800s stencils that looked like they would be a good fit for this space." Q. How long did it take you to complete the project? Were you surprised by the time frame? A. "Well, we started with the fireplace stenciling when the Tavern Room officially opened in July, and it was a very quick 1-hour process. Very few stencils were put up, but it gave an idea for people to see what was to come! I got started on the more in-depth stenciling in September, and there is one more large stencil I am waiting on at this time. Then I think the room will be done. But, maybe not! I'm still looking around seeing some bare spaces that need to be filled. Some of the pictures I saw of old Tavern Rooms , well the walls were covered COMPLETELY in stencils! It looked like wallpaper. I was amazed looking at them thinking it must have taken them such a long time to do all of that. But, that's how they did then. Wallpaper was very expensive back then. Stenciling was an inexpensive way to get that same look and pattern. As I look around in here, I think, "Yeah, there is quite a bit in here, but I can still do more!" This was the first time I had done anything like this, so I really did not have a timeline in mind. But in the back of my mind I though it was probably going to take me about a month. Hahahaha, and I went well past that! I found some of the patterns to be very tedious and time consuming. The ones that I thought would be the easiest tended to be the ones that were the most time consuming! It took a little longer than I anticipated, but in the end, I think it was worth it." Q. Have you ever done a project like this in a historical space/home? Tell us a little bit about your background with interior design? A. "I had never done anything like this in a historic space, but I did do interior design projects for private homes. Not so much stenciling, but sponging was very popular when I did interior design back then. And I did sponges that were very similar to the stencils -- and sponges gave a finished look too, just like the stencil do. This was kind of a first time with this type of project." Q. What was your favorite part about the stenciling project? What was a bit of a challenge -- if anything? A. "I enjoyed seeing it all come together, because it really wasn't planned...it really kind of came along as I went from part to part in the room. I let the room dictate to me what it needed. There are parts from different things in the room that are put together. The hardest part was figuring out the measurements. That was the part I most disliked. It took me a few days of measuring and remeasuring -- one wall is bit longer than the other so I had to fit the same patterns into spaces with different measurements. But, I bet that you can't tell which wall was bigger -- and guess what, I am not going to tell you!" Q. As our main docent, what have been some of the comments you’ve heard from our visitors during your tours of the space? A. "Everyone seems to really like it! I have not heard anything negative at this point. People tell me that they like this room before they even know I had anything to do with it. People have said that this room makes them feel comfortable. I notice that people tend to linger in the room, too -- they take longer in the space -- they are not in any rush to get out. Sometimes I have to encourage people to go into the next room, the next exhibit space to keep things moving for the tour. Hahahaha! They just want to stay in here, and often times, they will revisit the space again once the tour is over. I even had a gentlemen walk into the museum specifically asking to see this room. He had heard about it, and he wanted to see it for himself in person. I feel that this room has done the purpose of what we all had hoped it would -- what it was intended to do. And that makes me glad -- it had done what I hoped it would do." Thank you Deb, for all of your hard work at bringing the Tavern Room alive with color and vibrancy! After learning about historic stenciling from Deb, are you interested in beginning your own project? Well, you're in luck! Come visit the Greenbrier Historical Society Library and Archive and take a look at our copy of Early American Wall Stencils in Color. You just may find a pattern that inspires your inner artist! We are open from 10:00-4:00 Tuesday through Saturday -- please call ahead to make an appointment. And here are some helpful tips, too if you are looking to start your own project:

Are you are interested in seeing our Tavern Room stenciling in person? We hope that you can come visit us! You can try your hand at writing with quill and ink, or attempt a game of historic loo with your group. For those of age, you can even come join us during First Fridays and other special events and special occasions, and enjoy Greenbrier Valley Brewing Company's Ole Ran'l Pilsner on draft in the Tavern Room. We look forward to seeing you there, one day soon... Deb Marquis-Cascio Bio:

Deb had lived in Connecticut her whole life until she moved to Maxwelton 8-years ago. Her and her husband of 9-years, Greg, moved to West Virginia when Greg took a job at the hospital. Before joining us at the Greenbrier Historical Society, Deb was an interior designer for a high-end retailer and also worked on the side on both large and small design projects. Deb left the design field around 1988 to work for a doctor. She continued her work as an office manager for 20+ years until leaving the field in 2005. Deb has two daughters, Danielle and Melissa, and two grandkids, Elizabeth and Gabriel. One of Deb's personal projects is sewing burial gowns for stillborn babies out of donated wedding dresses. She has truly been a great asset to the Greenbrier Historical Society over the last 3.5 years.

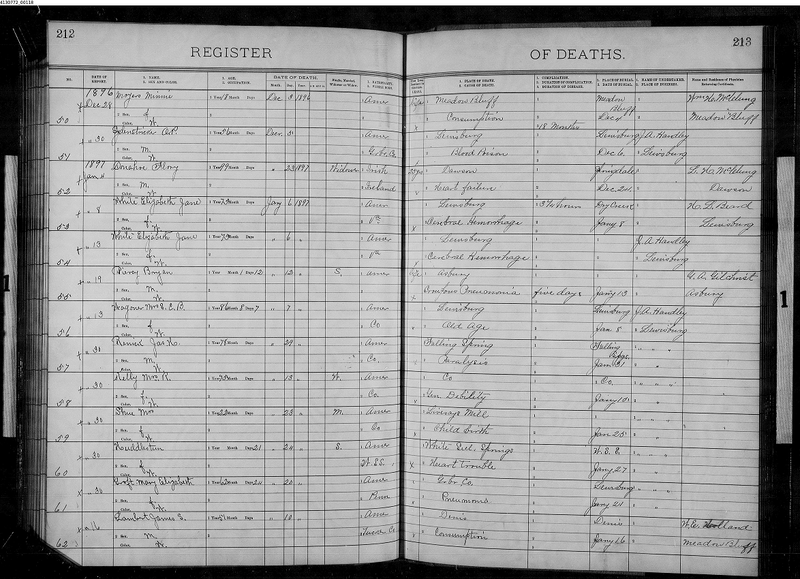

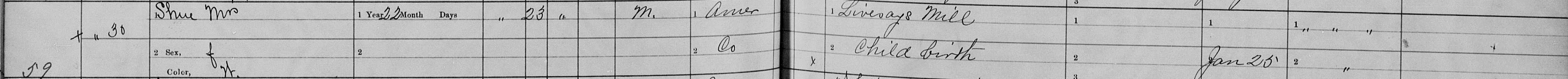

0 Comments

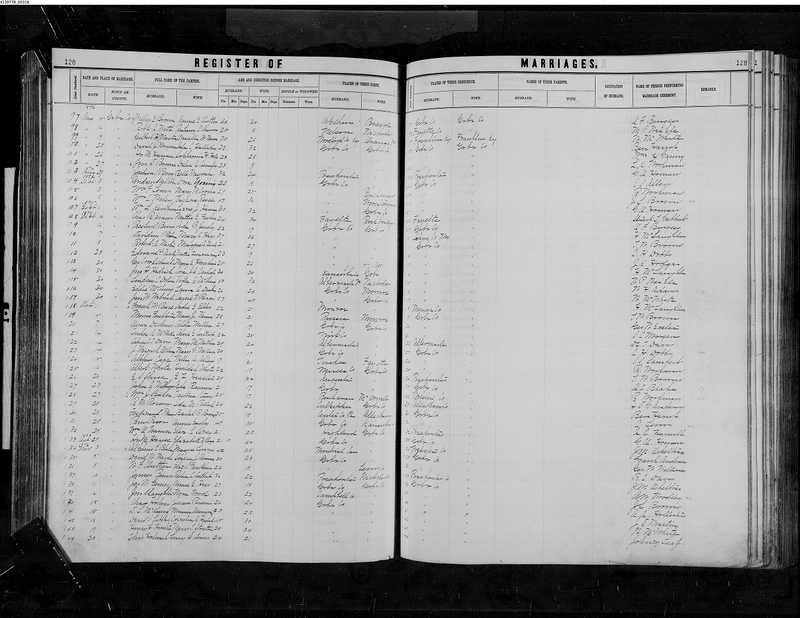

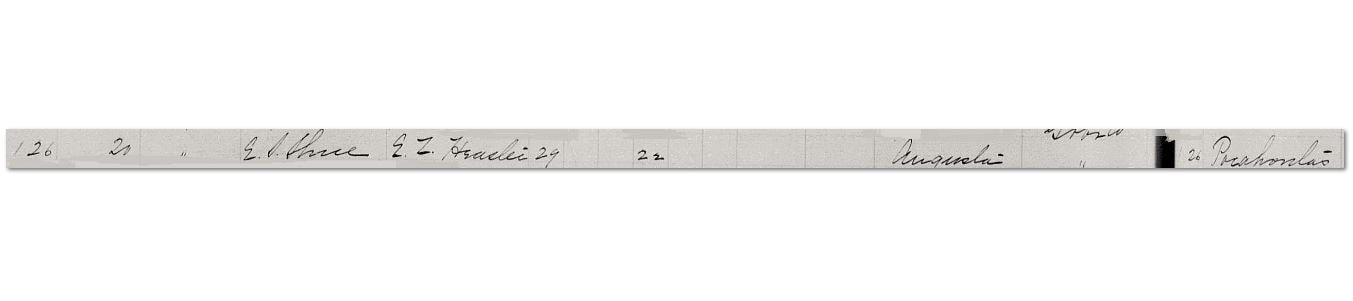

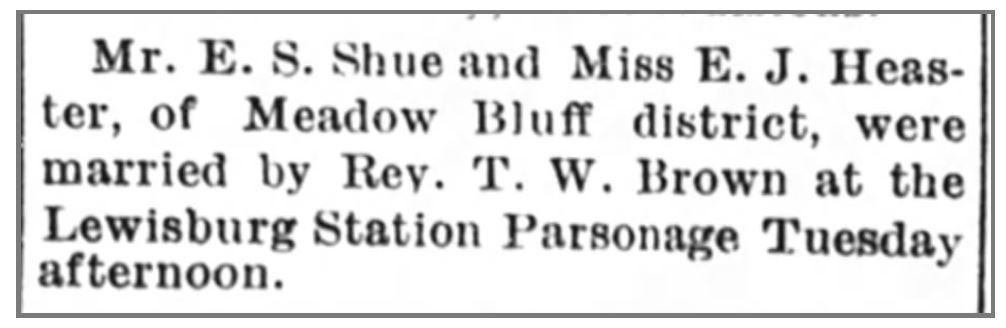

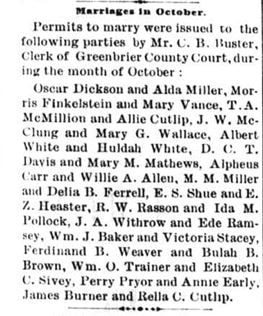

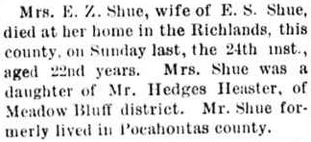

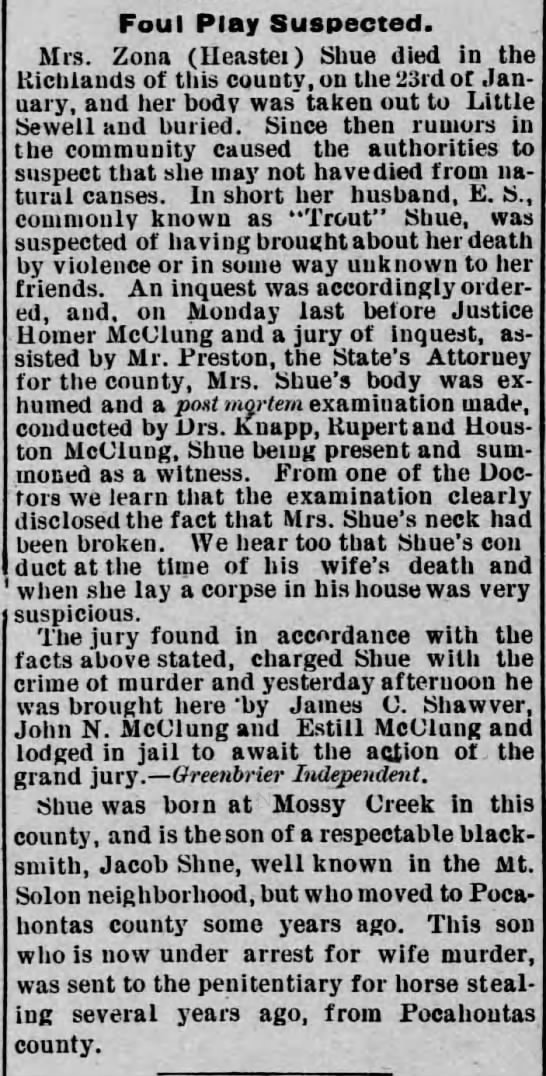

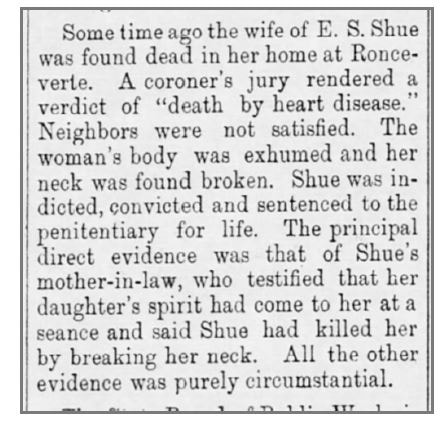

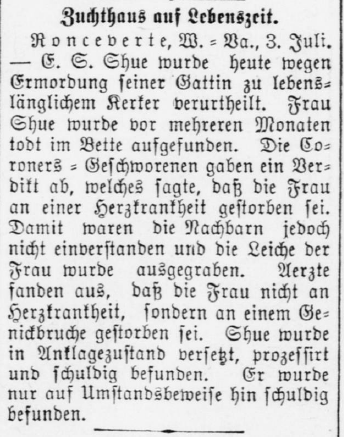

The Greenbrier Ghost Reexamined by Arabeth Balasko The tale of the Greenbrier Ghost seems like your classic tragedy – featuring a lifeless young bride, her dubious husband, and her bereaved mother; however, this January 1897 murder investigation would end up being anything but textbook. Although it is famous as the only instance in history where testimony from beyond the grave led to a murder conviction – clearly, there is more to this story than just the supernatural. [1] When I began to review the tale of the Greenbrier Ghost, I quickly found that there was an abundant amount of contradicting and conflicting information in the written record, which I found fascinating. Each story had its own spin on how the death of Elva Zona Heaster Shue happened. I then began to think, with such conflicting information, how is one to find the facts, the truth, when all the resources seemed to be recounting a different story? As an archivist and historian, I am always looking for the facts. “How do I get to the truth of what really happened?” However, with the endless conflicting newspaper accounts, the missing primary resources and crucial documents, and the fact that there are no longer any survivors from the time this case was tried – I sadly have not found any real answers, but I certainly have come up with many new questions. Before we get into this very strange account which has been told and retold over the last century, I wanted to share why I wanted to reexamine this particular case, 125-years after the fact. Archivists always enjoy highlighting their repository’s unique holdings and collections. By showcasing these "hidden treasures," archivists aspire to challenge users to think about where that information comes from. Where do these materials and resources originate? How have they been used over the years? How have they been made accessible for use? How do you find information? By assessing archival materials, it encourages the archivist and the archival users to reevaluate what they have heard and start a search for the facts, the truth of the matter. [2] Speaking of getting to the truth of the matter -- will anyone ever be able to truly solve the mystery of what happened to Zona that fateful day in January 1897? 125-years later, here is my attempt at sharing some new insights and questions to ponder so that you yourself can reflect and decide what you think happened... “The dreams which reveal the supernatural are promises and messages that God sends us directly: they are nothing but His angels, His ministering spirits, who usually appear to us when we are in a great predicament.” – Paracelsus In October 1896 in Greenbrier County, West Virginia – in a small area known as the Richlands the newly married Elva Zona Heaster Shue (she was referred to as Zona) and Erasmus Stribbling “Edward” Trout Shue (he is often referred to as E.S. or Trout) set-up a life together in a two-story home at Livesay’s Mill. Although they apparently had not known each other long before their marriage, all seemed to be well. He was employed and seen as a talented and respected blacksmith at Livesay’s Mill, and she was a homemaker and was well-known locally around the small community of the Meadow Bluff and Richlands region. It was not until her untimely demise that winter that rumors began to circulate around town of how others in the community truly perceived Trout and his marriage to Zona. [3] While he is often described as a man who was new to the county, his family had a homestead that was located on Droop Mountain, which borders both Pocahontas and Greenbrier Counties. Additionally, before he was married to Zona, Trout had two other wives – both from locally known families. His first marriage to Allie E. Cutlip ended in divorce – and his second marriage to Lucy Ann Tritt ended with her death. There are currently no identifiable official death records for Lucy Ann Tritt, therefore, her cause of death is unknown at this time, but it was a circulating rumor around town that Trout had somehow been responsible for her death. [4] Therefore, when Zona ended up dead only three months after they were married, and Trout was acting suspicious according to the onlookers at Zona’s wake, rumors began to spread all around town that Trout “must have had” something to, do with it. So, what exactly happened to Zona that ill-fated winter day? Here is the story, as it has been told so many times before… On a chilly Saturday morning, January 23rd, 1897, a young African American neighbor of the Shue’s, Anderson “Andy” Jones was asked by Trout several times to stop by the Shue’s house to run an errand of gathering eggs. When he finally made it to the Shue’s homestead, he felt something wasn’t right. The house was dark and quiet – so he went in looking for Zona, as Trout had asked him to see if “Mrs. Shue wanted anything.” He apparently called for her, and when she did not answer, he went inside to look for her. According to one report, he had found her lifeless body laying at the bottom of the stairs. He then ran down the road to his home and told his mother, Martha, what he had found. When word finally got to Trout that something bad had happened to Zona, he supposedly hurried home and found her dead. Onlookers reported that Trout had acted inconsolable and told everyone to leave the house and call for Dr. Knapp (the local doctor) to come to his home. It was then reported that an hour or two had elapsed before Dr. Knapp arrived to the Shue’s home, and during that time, Trout had already clothed Zona in a dress with “a high-collared neck, and a large veil several times folded and tied in a large bow under the chin,” and placed her body into their bed. This did not seem to arouse any suspicion from the doctor, and he did try to “resuscitate” Zona; however, it was clear that she was dead. Upon his initial examination, Dr. Knapp supposedly stated that Zona’s cause of death was heart disease or everlasting faint; however, in the official Greenbrier County Death Book, her listed cause of death was childbirth. It was also reported that Dr. Knapp had been treating Zona for weeks before for some ailment but there are no records showing this – nor was Dr. Knapp’s signature or comments listed on the official death record for Zona. In fact, her name is not even listed in the official record, she is simply identified as “Mrs. Shue.” [5] After her body was fully examined, Zona was taken to her family’s home on Little Sewell Mountain to prepare for a wake and a prompt burial in the coming days. However, when her body arrived it was noted that her mother, Mary Jane Robinson Heaster, expressed that she felt Trout had something to do with her daughter’s untimely demise. In fact, during the wake folks began to notice how affected Trout was by Zona’s death – some found it admirable and it seemed to show just how much he had loved his late wife. Others, such as Mary Jane, felt it was unnatural the way he acted – it was reported that he was acting overly erratic and theatrical – it is stated that he even banned anyone from touching his wife’s body. He would always be closely to the casket and folks began to notice that Zona’s neck had an unnatural look – loose and wobbly – and she had a bruise on her cheek that seemed to just appear out of nowhere. Though there was talk going around the community about Trout, his bad temper, and his odd actions around the wake and funeral, it seemed to be a closed case – an unfortunate circumstance – that was all. [6] Mary Jane was not satisfied with this conclusion – she felt in her body and soul that something bad had happened to Zona. After Zona died, Mary Jane went into a state of severe grief and constant prayer, begging her daughter to appear to her and tell her what had really happened. She is quoted as saying, “I prayed to the Lord that she might come back and tell me what had happened; and I prayed that she might come herself and tell on him.” According to Mary Jane, she began to have visions where Zona appeared to her and told her the following, “He was mad that she didn’t have no meat cooked for supper […] and she said I had plenty; don’t you think that he was mad and just took down all my nice things and packed them away and ruined them. […] She cames four times and four nights; but the second night she told me that her neck was squeezed off at the first joint and it was just as she told me.” [7] After her visits from Zona, Mary Jane went to the courthouse to talk to Greenbrier County’s prosecuting attorney, John Alfred Preston. She informed him that something was not right and begged him to look further into her daughter’s death. Ultimately, an inquest was made and an exhumation was planned. When Zona’s body was exhumed, it was discovered that she had suffered a broken neck, a finding which had been overlooked upon initial examination. Trout was present at the exhuming, and his actions were once again labeled “suspicious,” and as a result of the new findings, Trout was immediately placed under arrest for Zona’s murder. [8] The next few months were full of town gossip, more character assassinations and accusations – in May Trout supposedly threatened to kill himself while he was in prison awaiting the trial. Every few weeks the build-up to the trial was printed in the Greenbrier Independent. Finally, five-months after Zona was found dead, her husband, Trout went on trial for her murder. [9] At his trial, Trout took the stand, but it was apparently met with unease. It is reported in the Greenbrier Independent, July 1st, 1897 that, “Shue was on the stand all Tuesday afternoon. He was given free reign and talked at great length; was very minute and particular in describing unimportant incidences […] said the prosecution was all spite work; entered a positive denial of the charge against him; vehemently protested his innocence calling God to witness; admitted that he had served time in the pen; declared that he dearly loved his wife; and appealed to the jury to look into his face and then say if he was guilty. His testimony, manner, &c. made an unfavorable impression on spectators.” [10] When Mary Jane Robinson Heaster was called to testify, she shared the experiences of her daughter contacting her from beyond the grave to tell her how she had been murdered by Trout. She also gave detailed descriptions of Zona's house and the land surrounding the property, despite claiming that she had never visited her daughter's residence. Her testimony was powerful and compelling, and since Zona’s mother was a well-known pious and Christian woman around town, her testimony was accepted as truth, and these powerful accounts became the case’s strongest evidence. After the jury heard both sides of the testimony, they recessed for “1 hour and 10 minutes,” and came back with a guilty verdict for murder in the first-degree. It is quoted in the Greenbrier Intependent, July 8th, 1897 edition that “Though the evidence was entirely circumstantial, the verdict meets general approval as all who heard the evidence are satisfied of the prisoner’s guilt.” [11] Trout was sentenced to life in the West Virginia State Penitentiary in Moundsville, some local folks felt that justice had not been entirely served and wanted to take matters into their own hands. They felt that he should have hanged for what he did to Zona, and a lynch-mob was formed by some local townsfolk including C.G. Martin, J.L. Nary, Robert Hunter, and Otey Arbaugh. The plan was to go to the county jail, where Trout was held, “take him outside and hang him.” A local man, George Harrah, who lived near the Meadow Bluff area where the mob had formed, found out about the lynch mob’s plans to overtake the jail. He quickly rode to the local sheriff’s house, Sheriff Nickell, who also lived in Meadow Bluff, in an attempt to stop the mob before they set off for the jail. In the July 15th, 1897 edition of the Greenbrier Independent the mob incident is reported as follows: “Mr. Nickell and Mr. Harrah then started for Lewisburg, and had to pass the campground where the lynchers were to assemble. When they arrived there, which was about 9 o’clock, several of the mob were already there. – They passed by safely but were recognized. Several minutes later four of the mob pursued and after an exciting chase overtook them, presented pistols, and demanded that they stop. The Sheriff drew his pistol and was in the act of firing when he recognized his assailant, and not desiring to hurt or kill him concluded to try moral suasion. – He and Harrah surrendered and were taken back to the residence of Mr. D. A. Dwyer, where after considerable parleying, the Sheriff succeeded in inducing them to disband and return to their homes. They were provided with a stout new rope, were armed with Winchesters and revolvers, and numbered from ten to twenty, as far as could be seen – the most of them keeping in the background in the shadows of the trees.” [12] The irony of the situation is that even if the mob had succeeded in storming the jail in Lewisburg in an attempt to lynch Trout, they would have only found an empty cell. Having gotten word that a mob was forming, Deputy Sheriff John G. Dwyer was able to take Trout to, “a place of safety in the woods a mile or two outside of town.” After the foiled lynching, Trout was then escorted to the West Virginia State Penitentiary in Moundsville, where he died in the spring of 1900 reportedly from an outbreak of tuberculosis at the prison. [13] Was Trout really guilty of murdering his wife Zona because she didn’t cook meat for supper? Could Zona have died in childbirth, as the official death record stated? The young boy, Andy Jones who found Zona, had supposedly reported she was laying on the floor – could she have somehow fallen and broken her neck? Did Zona really come back from the grave and tell her mother that Trout murdered her? Was the outcome of this case justice from beyond the grave? Or, was it a witch-hunt – a quest to prove that a man known around the community to be of ill repute was to blame for his wife’s unexpected and untimely demise? The facts as they stand are very limited. Regarding Zona, it is known that she married Trout on Tuesday, October 21, 1896, and that they were married only a little over 3-months before she died. It is known that there are conflicting dates reported for Zona’s death – on the official death record which has her death date listed as Saturday, January 23, 1897 and the newspaper accounts which have her death date listed as Sunday, January 24th, 1897. It shows on the official record of her death, that her cause of her death was listed as childbirth. It is also known that Zona had a baby boy out of wedlock on November 29th, 1895, which was almost a year before she and Trout had ever met. [14] Regarding Trout, it is known that he never seemed to conceal or hide the fact he had a previous criminal record for stealing a horse, and he did not hide the fact that he was a divorcee and a widower before he married Zona. It is also known that it was not until Mary Jane had her visions that he was even suspected for murdering Zona and her body was exhumed. It is known that he proclaimed his innocence and that he was held in the prison in Lewisburg until his June 1897 trial took place – and that he was sentenced to the West Virginia State Penitentiary in Moundsville for the “rest of his natural life” for the murder of Zona. [15] One of the six jurors present during the exhuming of Zona’s body, C. G. Martin, was a self-described neighbor and friend to Mary Jane who stated in an October 11th, 1897 letter to Richard Hodgson (Secretary of the American Society for Psychological Research); “Mrs. M. J. Heaster told me about her vision or dream ten days to two weeks before the body of her daughter was taken up and examined. I was one of the six jurors at the examination of the body and heard her testimony before she knew anything of what we had found. [..] In short I would say upon examination we found every iota just as Mrs. Heaster had told several others and myself beforehand except in the hollow as located above and behind the plank in the cellar we found nothing although diligent search was made. [..] Mrs. Heaster is a nigh neighbor of mine, a daughter of an English sailor, and as daring, gritty woman as I ever saw.” [16]

It was also this same man, C. G. Martin who was identified in the July 29, 1897 edition of the Greenbrier Independent as one of the members of the lynch mob that was summoned to the Circuit Court to account for his intended actions again Trout. [17] Those are the facts. Very limited in nature, and mostly circumstantial. As an archivist, I believe in following the records; however, I have found that with this case, the primary resources, records, and documents outline a confusing story – one that is peppered with few facts and several strong feelings. It is clear in Mary Jane’s testimony that she felt in her body and soul that Trout had murdered her daughter – it is also apparent that many in the county also felt that Trout was guilty – he was not to be trusted or believed – he was a stranger. Those who had witnessed against him were viewed as good, Christian folks, they were known in the community, and were reliable. Their words and testimonies were believed, they were trusted…they meant something. Maybe we shall never know the truth of what happened to Zona. Regardless of the truth, it is a fascinating story about the relentlessness of a mother's love, the miscarriages of the justice system, the power of personal persuasions, inherent feelings and biases about those whom we perceive as evil, and the overwhelming need for society to have a villain who fits the typical criminal profile. Citations and Footnotes: [1] It is reported that this case is the “Only known case in which testimony from a ghost helped convict a murderer.” – https://wvtourism.com/ghost-who-gave-legal-testimony/ [2] Each of the newspaper accounts seemed to have a different sensationalized spin on how this event unfolded. In fact, this story has been revisited numerous times over the decades/century after the events took place. Each story seemed to be more outlandish than the last. In a 1966 The Orlando Sentinel (Orlando, FL, 20 Nov 1966, Page 99) article by Frank Edwards, Zona was even described as “a beautiful, teen-age blonde.” As the event got further and further away from the present day, the recounts of what happened that day and the search for truth became harder and harder to uncover. [3] In Katie Letcher Lyle’s 1999 novel, The Man Who Wanted Seven Wives The Greenbrier Ghost and the Famous Murder Mystery of 1897, she used a mixture of truths and fictionalizations to describe the scenarios surrounding this case. The information regarding the Shue’s home and their standing in the community was confirmed and reported as facts by both her and other sources. [4] The Greenbrier Historical Society and North House Museum Archive has the original marriage bond for E.S. Shue and Allie E. Cutlip. The bond is signed by E.S. Shue, and witnessed by Joshua Sharp – “x” – it was approved and signed by Charles B. Buster, County Clerk of Greenbrier County in 1885. This bond proves that Shue was present in Greenbrier County in the 1880s and was not a total “stranger” who roamed into town out of nowhere in 1897, which is what is often reported. To learn more about Charles B. Buster’s role of County Clerk, please visit: http://www.us-data.org/wv/greenbrier/bios/buster_charles-b_1838-1929.txt -- Primary resource documents are not available showing when Shue and Tritt were married, but according to Lyle’s book, there are newspapers articles from the Pocahontas Times reporting Tritt’s death, “ 2-15-1895 – Mrs. E.S. Shue, wife of ‘Trout’ Shue died very suddenly at her home near here on last Monday morning the 11th. We haven’t been able to learn the particulars of her death.” Pp. 71 [5] There have been several notations regarding Trout’s odd behavior around dressing his wife, acting “possessive” of her body, etc. which has been reported in an 1897 newspaper articles from the Greenbrier Independent July 01, 1897 edition. To read the full excerpt, please visit: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84037217/1897-07-01/ed-1/seq-3/ as well as an article in the Staunton Spectator and Vindicator. It was noted in the official Death Record for Zona, that she died in “childbirth.” The Death Record also only identifies her as “Mrs. Shue” and there is not a doctor listed; however, the Handly Undertaking Company in Lewisburg was listed as the official undertaker. -- Zona’s death announcement also appeared in the Greenbrier Independent 01/28/ 1897 edition: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84037217/1897-01-28/ed-1/seq-3/ In this article it is stated that she died on “Sunday the 24th;” however, her death is recorded as happening on” Saturday, January 23rd, 1897” in the official record. This again shows the differences found among the available records and resources for this case. [6] Lyle’s mentioning of Zona’s wake was confirmed and reported as facts – however; it has also been reported as fact in the Greenbrier Independent that there seemed no cause for suspicion until Mary Jane Heaster reported her “visits from Zona” to the County authorities that led to Zona’s body being exhumed. [7] This excerpt was taken directly from Mary Jane Robinson Heaster’s testimony which was printed in the Greenbrier Independent 07/01/1897 edition. To read the full excerpt, please visit: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84037217/1897-07-01/ed-1/seq-3/ [8] Ibid. [9] It was reported in the Greenbrier Independent 5/20/1897 edition that “Trout” Shue who is now in jail here awaiting trial for the murder of his wife, has threatened to kill himself.” https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84037217/1897-05-20/ed-1/seq-3/ [10] Although E.S. “Trout” Shue’s testimony was not fully provided in this article, it did highlight his erratic and strange behaviors while taking the stand. These comments were printed in the Greenbrier Independent 07/01/1897 edition. To read the full article, please visit: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84037217/1897-07-01/ed-1/seq-3/ [11] This statement was printed in the Greenbrier Independent 07/08/1897 edition. To read the full article, please visit: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84037217/1897-07-08/ed-1/seq-3/ [12] This excerpt was printed in the Greenbrier Independent 07/15/1897 edition. To read the full article, please visit: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84037217/1897-07-15/ed-1/seq-3/ These individuals were also IDed on the July 12th, 1897 Court Case “The State of West Virginia vs. Warrant -- John Seward, Otey Arbaugh, John Nary, CG Martin, John Thompson, Robert Hunter, Cassie Bivens, and Marshall Heaster and others whose names are unknown of the said county, did unlawfully combine and conspire together for the purpose of inflicting punishment and bodily injury upon E. S. Shue then confined in the jail of Greenbrier County under sentence for murder: These are therefore in the name of the State of West Virginia to command your forthwith to apprehend and bring before me the body of the said John Seward, Otey Arbaugh, Cassie Bivens and Marshall Heaster, John Nary, C G Martin, John Thompson and Robt Hunter to answer the said complaint, and to be farther dealt with according to law. Given under my hand and seal this 12th day of July, 1897.” The 1897 Court Case document can be found in: The Greenbrier Historical Society Archives, Greenbrier County Courthouse Collection, July 12, 1897; Box 1890-1899. [13] This statement was printed in the Greenbrier Independent 07/08/1897 edition. To read the full article, please visit: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84037217/1897-07-08/ed-1/seq-3/ [14] According to the WV State Birth Records, Zona had a baby boy born on “November 29th, 1895.” Under the name of the father the record reads “Supposed to be George Woldridge.” The state website has her name listed as “Zoma;” therefore, the record does not populate with a search for “Zona Heaster.” The record also identifies Zona as being “22 years old;” however, in her 1897 death record, her age is also listed as “22 years old.” Once again, the official records provide an unclear picture of what is fact and what is fiction. http://archive.wvculture.org/vrr/va_view.aspx?Id=499632&Type=Birth [15] This statement was printed in the Greenbrier Independent 07/08/1897 edition. To read the full article, please visit: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84037217/1897-07-08/ed-1/seq-3/ [16] In Katie Letcher Lyle’s 1999 novel, The Man Who Wanted Seven Wives The Greenbrier Ghost and the Famous Murder Mystery of 1897, she discusses in Appendix VII: Visions Resulting in Conviction for Murder, a study that was conducted by Richard Hodgson, while he , “…served as secretary of the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR)” during the fall of 1897. These letters contain written responses from a variety of folks involved or close to the Heaster family, including C.G. Martin, who claimed to have been “…one of the six jurors at the examination of the body (of Zona) and heard her testimony before she knew anything of what we had found.” He was also a self-proclaimed neighbor and friend of Mary Jane Robinson Heaster. Pp. 183-190. [17] As stated above in footnote 12, C.G. Martin was one of the identified members of the lynch mob that attempted to hang Shue after his trial had ended. Early Queer History of the Greenbrier ValleyBy Sarah Shepherd - Archive Associate “Of course, sex has been all things in all periods…But on the whole, the farm enjoyed sex more, respected it more, and discussed it less…Sex was like groceries…most of the people stored their supplies at home. And county eating is lush and good. I have never understood this much-bruited Puritanism. We were Presbyterians of the deepest dye, running to clergymen and elders and tenders of out-post Sunday Schools. But I do not recall any adults who worried about their immortal souls (the Lord would tend to that) nor about their sexuality; the Lord had already tended to that.” |

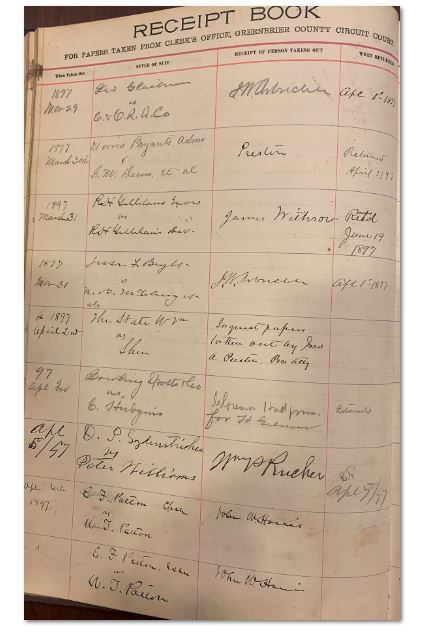

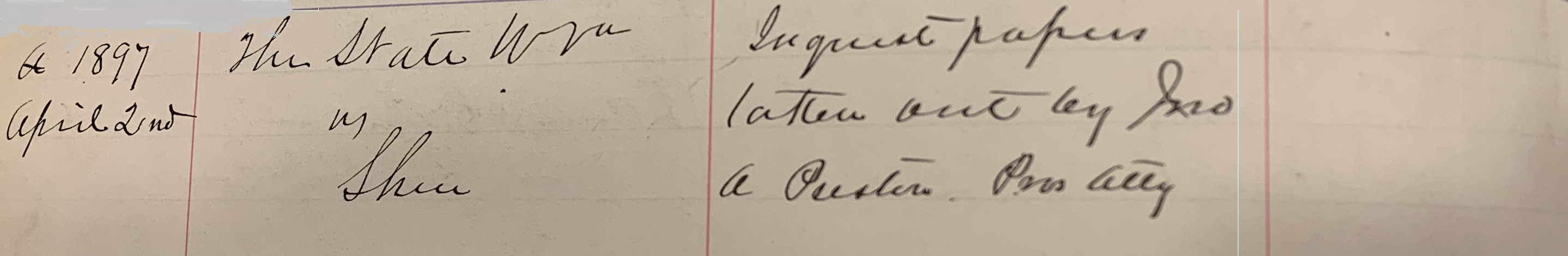

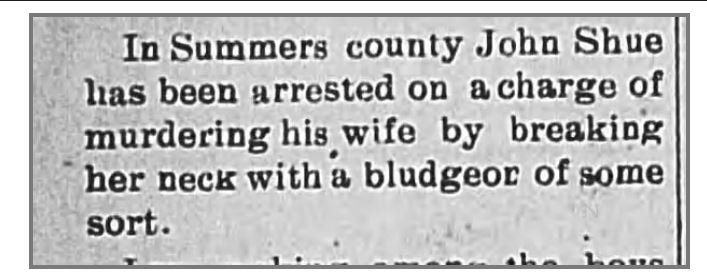

| The focus on sodomy meant that women were not arrested as much as men. However, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, a political radical who was sentenced to two years in the Alderson Federal Women’s Prison in 1951, described lesbianism in the prison in her memoir. She described how “the women walked two-by-two, as directed by the officer. But they chose their own partners and woe betide anyone who tried to cut in on an unmistakable lesbian pair… |

| In the dark of the movies these pairs held hands and kissed passionately, and walking home hung behind the lines, behaving in a lover-like fashion.”[18] While some of these relationships were temporary, other women exchanged rings and called each other husband and wife.[19] Flynn described one woman who grew up in Alderson and both her and her sister were lesbians. She was in a relationship with another woman. Her lover broke it off when she fell in love with a man, but he deserted her when she became pregnant. The two women resumed their relationship and raised the child together. The mother eventually married someone else when their son was five, but the boy kept in touch with his other mother.[20] |

Walter Freeman

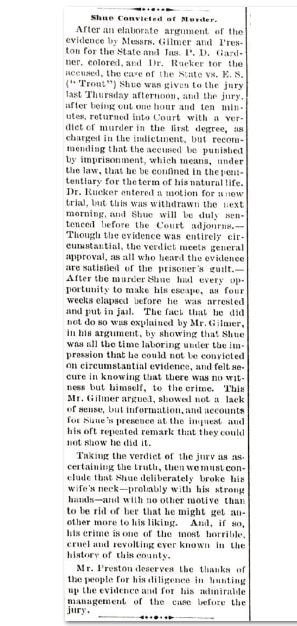

Walter Freeman Prison in the early 1900s were harsh and some men chose the mental institution instead. Bill Richards, a Charleston florist, chose the mental institution, despite knowing that he was not crazy for being gay, and was locked up in maximum security for several months in the late 1960s.[21] The institution was not safer. Homosexuality was considered a medical disorder and doctors would apply electric shock therapy and even perform lobotomies to try to cure people. Walter Freeman, who invented the ice pick lobotomy, operated in West Virginia. The Smithsonian Magazine recorded that around forty percent of the thousands of lobotomies that Freeman performed were on queer people.[22] These operations had varying consequences including death and severe disfunction.

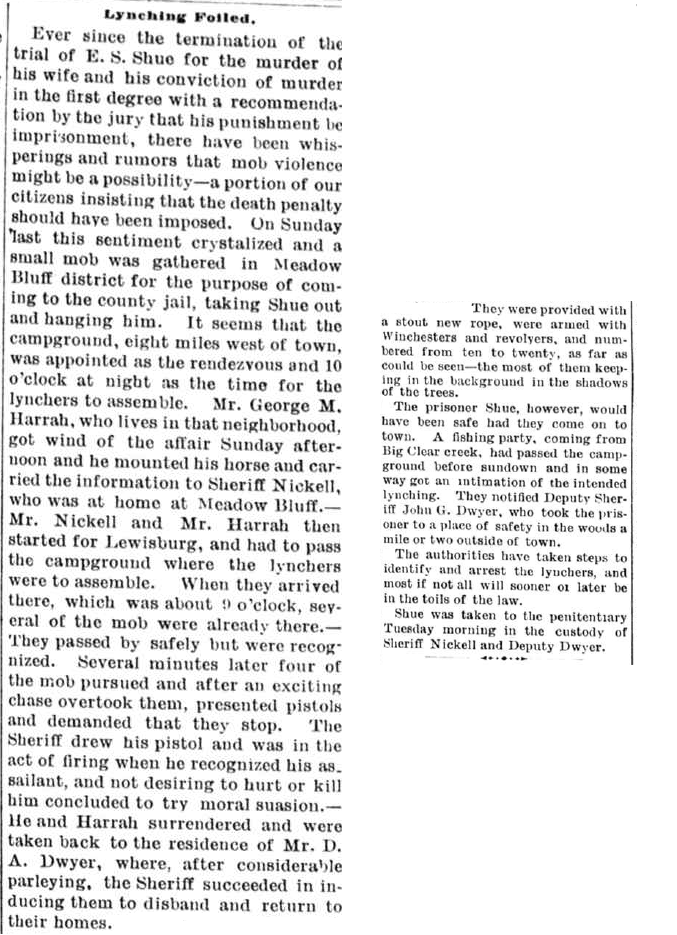

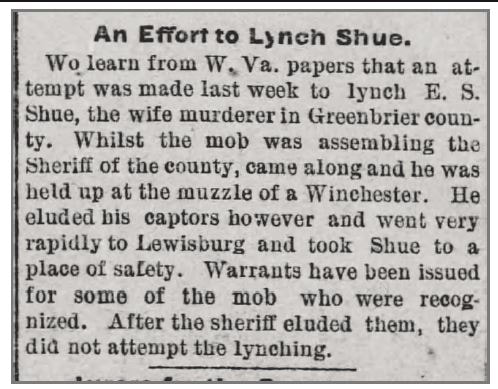

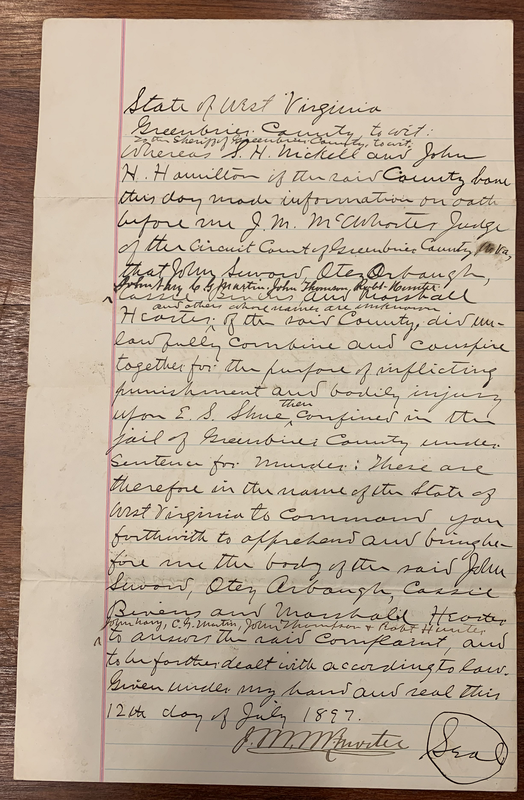

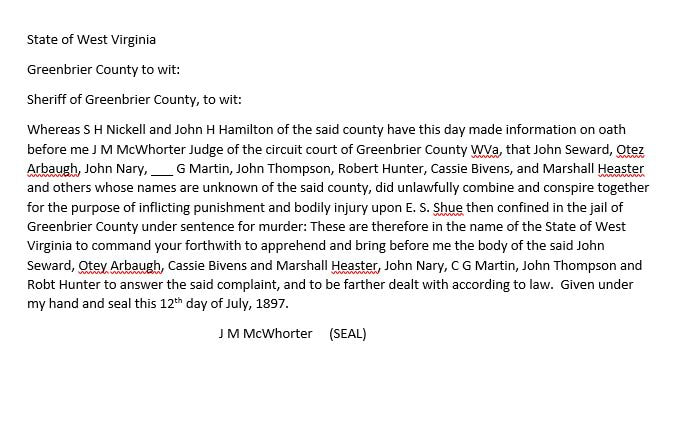

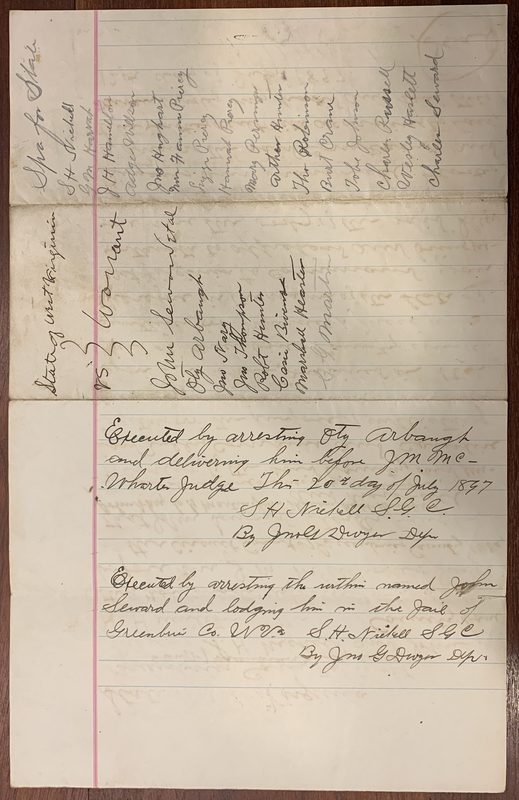

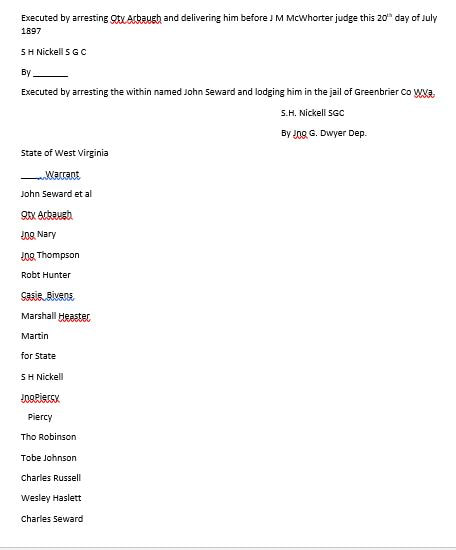

In Greenbrier County, there were five known convictions of sodomy. Five men were convicted from 1950 to 1963 with their names and crime posted in the public newspaper, the Greenbrier Independent.[23] At this time, the Greenbrier Independent’s motto was “Nothing Shall be Indifferent to Us Which Advances the Cause of Truth and Morality or Which Concerns the Welfare of the Community in Which We Live.”[24] These men were forcibly outed to their community as all indictments were listed on the front page. West Virginia did not repeal its sodomy law until 1976.[25]

In Greenbrier County, there were five known convictions of sodomy. Five men were convicted from 1950 to 1963 with their names and crime posted in the public newspaper, the Greenbrier Independent.[23] At this time, the Greenbrier Independent’s motto was “Nothing Shall be Indifferent to Us Which Advances the Cause of Truth and Morality or Which Concerns the Welfare of the Community in Which We Live.”[24] These men were forcibly outed to their community as all indictments were listed on the front page. West Virginia did not repeal its sodomy law until 1976.[25]

Other Literature on Appalachian and West Virginian Queer History

| Rebecca Baird, Kathryn Staley, and Jeff Mann, “Mountaineer Queer: An Interview with Jeff Mann,” Appalachian Journal, Vol 35. No 1/2 Fall 2007/Winter 2008 Kate Black and Marc A. Rhorer, “Out in the Mountains: Exploring Lesbian and Gay Lives,” Journal of Appalachian Studies Association Vol 7. 1995 Jeff Mann “Stonewall and Matewan: Some Thoughts on Gay Life in Appalachia” in Journal of Appalachian Studies, Vol. 5, No. 2, Fall 1999 Edge: Travels of an Appalachian Leather Bear, Harrington Park Press, 2003 Loving Mountains, Loving Men, Ohio University Press, 2005 “The Mountaineer Queer Ponders His Risk-list,” Appalachian Journal, Vol. 34, No. 3/4 Springs/Summer 2007 Binding the God: Ursine Essays from the Mountain South, Bear Bones Books, 2010 | “Risk, Religion, and Invisibility,” Journal of Appalachian Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2, Fall 2014 Silas House, “Our Secret Places in the Waiting World: or, A Conscious Heart, Continued,” Journal of Appalachian Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2, Fall 2014 Carrie Nobel Kline, Revelations, Huntington, West Virginia, 2001. This was a theatrical presentation about Appalachian resiliency in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered people written and produced by folklorist Carrie Nobel Kline. Read more about the project: https://www.folktalk.org/spoken-histories/glbt-stories/ Her collection of interviews of queer West Virginians are at Marshall University. Bradley Milam, Gay West Virginia: Community Formation and the Forging of a Gay Appalachian Identity, 1963-1979, Dissertation at Yale University, April 2010. |

References

[1] 1880 U.S. Census, Fort Spring, West Virginia, population schedule, p.23, dwelling 185, family 205, Mae Best, digital image, http://ancestry.com.

[2] Doug Hylton, “Ronceverte’s story connected with transgendered citizen,” Mountain Messenger, January 23, 2016.

[3] New York, New York, U.S., Extracted Marriage Index, 1866-1937, Maynard Best to Bryna Stacking Hunthall, June 30, 1906, http://ancestry.com.

[4] 1910 U.S. Census, Los Angeles, California, population schedule, p.1, dwelling 18, family 19, Maynard H. Best, digital image, http://ancestry.com.

[5] California, U.S., Death Index, 1905-1939, Dollie Best, death January 1, 1935, http://ancestry.com.

[6] “Fire at Cass,” Pocahontas Times, February 25, 1915.

[7] “Circuit Court,” Pocahontas Times, April 15, 1915.

[8] “The Strange Case of Max Curry,” Pocahontas Times, April 22, 1915.

[9] Marriage of Lillian L. Nethercutt and M. M. Curry, 1909, Vital Research Records-Marriage, West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture, and History, http://www.wvculture.org/vrr/va_mcdetail.aspx?Id=11100236.

[10] “The Strange Case of Max Curry,” Pocahontas Times, April 22, 1915.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Pocahontas Times, June 24, 1915.

[13] Pocahontas Times, August 5, 1915.

[14] Ibid.

[15] West Virginia, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1724-1985, Max Curry, probate date October 11, 1919.

[16] 1920 U.S. Census, Huntington, West Virginia, population schedule, p.14, dwelling 265, family 287, Lillian Curry, digital image, http://ancestry.com.

[17] Interview with Richard Weikel, conducted by Roland Layton, October 30, 2002, transcript pg. 7-8.

[18] Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, The Alderson Story: My Life as a Political Prisoner, (New York: International Publishers, 1963), 159.

[19] Ibid., 160.

[20] Ibid., 160-161.

[21] Trey Kay, “Us & Them: Locked up for Sodomy,” West Virginia Public Broadcasting, October 15, 2015, https://www.wvpublic.org/podcast/us-them/2015-10-15/us-them-locked-up-for-sodomy.

[22] “What it was like to be Gay during WWII,” Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/videos/category/history/what-it-was-like-to-be-gay-during-wwii/.

[23] “Circuit Court,” Greenbrier Independent, April 27, 1950; “Indictments Made,” Greenbrier Independent, April 28, 1955; “Grand Jury Indictments,” Greenbrier Independent, April 30, 1959; “Sentences Given,” Greenbrier Independent, May 15, 1958; “Circuit Court Indictments,” Greenbrier Independent, November 14, 1963; “Circuit Court Notes,” Greenbrier Independent, November 21, 1957.

[24] Greenbrier Independent, November 14, 1963.

[25] George Painter, “The Sensibilities of Our Forefathers: The History of Sodomy Laws in the United States,” Gay & Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest, https://www.glapn.org/sodomylaws/sensibilities/west_virginia.htm#fn9.

[2] Doug Hylton, “Ronceverte’s story connected with transgendered citizen,” Mountain Messenger, January 23, 2016.

[3] New York, New York, U.S., Extracted Marriage Index, 1866-1937, Maynard Best to Bryna Stacking Hunthall, June 30, 1906, http://ancestry.com.

[4] 1910 U.S. Census, Los Angeles, California, population schedule, p.1, dwelling 18, family 19, Maynard H. Best, digital image, http://ancestry.com.

[5] California, U.S., Death Index, 1905-1939, Dollie Best, death January 1, 1935, http://ancestry.com.

[6] “Fire at Cass,” Pocahontas Times, February 25, 1915.

[7] “Circuit Court,” Pocahontas Times, April 15, 1915.

[8] “The Strange Case of Max Curry,” Pocahontas Times, April 22, 1915.

[9] Marriage of Lillian L. Nethercutt and M. M. Curry, 1909, Vital Research Records-Marriage, West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture, and History, http://www.wvculture.org/vrr/va_mcdetail.aspx?Id=11100236.

[10] “The Strange Case of Max Curry,” Pocahontas Times, April 22, 1915.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Pocahontas Times, June 24, 1915.

[13] Pocahontas Times, August 5, 1915.

[14] Ibid.

[15] West Virginia, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1724-1985, Max Curry, probate date October 11, 1919.

[16] 1920 U.S. Census, Huntington, West Virginia, population schedule, p.14, dwelling 265, family 287, Lillian Curry, digital image, http://ancestry.com.

[17] Interview with Richard Weikel, conducted by Roland Layton, October 30, 2002, transcript pg. 7-8.

[18] Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, The Alderson Story: My Life as a Political Prisoner, (New York: International Publishers, 1963), 159.

[19] Ibid., 160.

[20] Ibid., 160-161.

[21] Trey Kay, “Us & Them: Locked up for Sodomy,” West Virginia Public Broadcasting, October 15, 2015, https://www.wvpublic.org/podcast/us-them/2015-10-15/us-them-locked-up-for-sodomy.

[22] “What it was like to be Gay during WWII,” Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/videos/category/history/what-it-was-like-to-be-gay-during-wwii/.

[23] “Circuit Court,” Greenbrier Independent, April 27, 1950; “Indictments Made,” Greenbrier Independent, April 28, 1955; “Grand Jury Indictments,” Greenbrier Independent, April 30, 1959; “Sentences Given,” Greenbrier Independent, May 15, 1958; “Circuit Court Indictments,” Greenbrier Independent, November 14, 1963; “Circuit Court Notes,” Greenbrier Independent, November 21, 1957.

[24] Greenbrier Independent, November 14, 1963.

[25] George Painter, “The Sensibilities of Our Forefathers: The History of Sodomy Laws in the United States,” Gay & Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest, https://www.glapn.org/sodomylaws/sensibilities/west_virginia.htm#fn9.

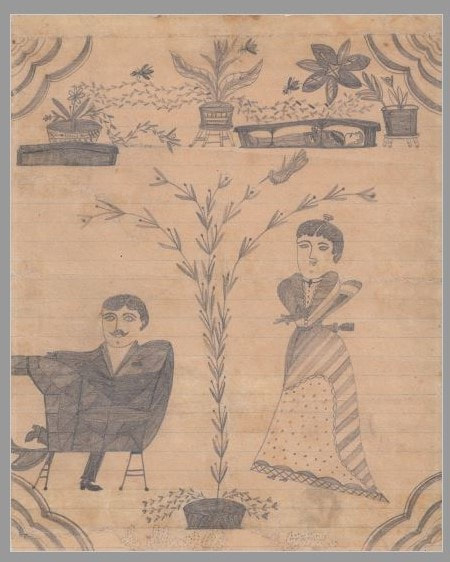

Lyda's Story featuring the Art of Greenbrier County's Lyda Reilly

by Jack Mayhew - classmate and friend of Lyda Reilly

Growing up in Greenbrier County instills one with a sense of pride that stays with you for the rest of your life. So is the life of Lyda Elizabeth Spencer Reilly, RN, an accomplished Artist. Born and raised on a farm located on Friars Hill Road, a few miles from the town of Renick, Lyda’s early days were filled with school and the attention of her grandfather Charlie Spencer who became her closest friend while he lived out his long life of ninety years with her family. In her early teen years, her family was expanded by the arrival of Linda and Brenda Spencer, her twin sisters who now reside in Lewisburg. As a young student, Lyda discovered art and was encouraged to develop her talent by her favorite teachers, Ms. Hanna and Ms. McKnight, which she did. However, her love of art took a back seat to her education. Immediately following High School she left the farm to attend nursing school.

Lyda Became a Registered Nurse (RN) and set about helping those in need. However, she never lost her love of farm life and her community which her paintings reflect. As soon as she had the opportunity she captured her family home on canvas. The painting now hangs on her bedroom wall in a location that ensures that it is the first thing she sees in the morning and the last at night.

Lyda expanded her life’s experiences with marriage and travel. The arrival of her daughter Kerry was magical and their bond has grown as they both excelled in the professions of helping others. Her daughter is now; Dr. Kerry Reilly, Ph.D.

Enjoy some of Lyda's art below:

Lyda Became a Registered Nurse (RN) and set about helping those in need. However, she never lost her love of farm life and her community which her paintings reflect. As soon as she had the opportunity she captured her family home on canvas. The painting now hangs on her bedroom wall in a location that ensures that it is the first thing she sees in the morning and the last at night.

Lyda expanded her life’s experiences with marriage and travel. The arrival of her daughter Kerry was magical and their bond has grown as they both excelled in the professions of helping others. Her daughter is now; Dr. Kerry Reilly, Ph.D.

Enjoy some of Lyda's art below:

Happy Earth Day: Sustainability at the North House Museum

By AmeriCorps Member - Abi Smith

Since the first Earth Day celebration in 1970, each April 22nd is an opportunity to reflect on environmental action and sustainability. As a historical society, we have a unique role to play in promoting sustainability. We like to joke that we’re always thinking in the past, especially when we deep dive into our research (or are running late). However, historical organizations also have a responsibility to consider future generations. If our mission is to preserve the diverse history and culture of the Greenbrier Valley, then sustainability is an inherent part of our mission statement. I decided to take some time this earth day to consider some ways in which we at the Greenbrier Historical Society could be more intentional in promoting sustainability.

| The first place that I looked for sustainable practices were in our archives and collections. Archives and collections are energy heavy organizations. Documents and artifacts are best protected in light and climate-controlled environments, but the maintenance of a climate-controlled environment takes a lot of energy. Often solutions to this problem include utilizing renewable energy sources like solar panels, or renovations that result in more energy efficient structures. While these are good goals, many of these solutions are most attainable by larger institutions. Smaller organizations typically have limited funds for energy efficient buildings and upgrades, particularly for those organizations that utilize historic buildings to store their collections. |

The issue of sustainable collection storage is particularly important in the communities of the Greenbrier Valley. The Valley experiences flooding disasters on a regular basis. Natural disasters, like flooding, can result in the loss of priceless information from private and public collections, as well as family documents. Sustainable collection storage would mean creating disaster plans and storage facilities that are less at risk to destruction. It might also mean working with local communities to create digital copies of private and family collections in case these physical items are destroyed. So how can small organizations work to promote sustainable collections.

One step that we can take here at the North House Museum is to be more intentional in our collecting. Did you know that many museums only display 10-20% of their collection? This means that large portions of a museum’s collection are sitting in climate-controlled storage. Although new additions to our collection are exciting, the constant growth of an organization’s collection is not always sustainable. A sustainable collection is one that an organization has enough staff, space, and time to manage. Museum collections are not intended to hold every artifact of a community’s history, but rather are to be curated collections that can be reworked as the needs of the organization changes. Here at the Greenbrier Historical Society, we are working to improve our collecting to focus on our scope of the Greenbrier Valley. This sometimes means deaccessioning exciting collection items that have no relation to our scope, like historic copies of the New York Times. We can deaccession these kinds of items with the knowledge this information will be preserved in other institutions with a more accurate collecting scope.

Preservation of information is a key part of our mission statement, but so is education. Museums are well suited for education as they are designed to communicate to diverse groups of people. Often, environmental sustainability is taught through the science of climate change. However, as a history focused organization, we also have space to teach sustainability. We can teach about historic land use and land management practices. In fact, our newest exhibit opening in May, The Road to Plenty, examines Native American land use and management, and how those practices changed with colonization. We can also teach about the impact of industry on West Virginia’s environment. The lumber and coal industries had a major impact on the land of the Greenbrier Valley, and the effects of these industries still impact our communities. By including discussions of sustainability into the programming we already have, we can provide a framework to help guests better understand the importance of sustainable practices.

The field of museums has been slow to develop sustainable practices. However, as more institutions begin to consider these issues, more museums are beginning to implement sustainability standards. The issues of environmental sustainability can seem overwhelming, particularly for small organizations. It may even make us question our understanding of how museums should operate. However, small, concrete actions will help shift museum and public practices and values to ones that help future community enrichment.

The field of museums has been slow to develop sustainable practices. However, as more institutions begin to consider these issues, more museums are beginning to implement sustainability standards. The issues of environmental sustainability can seem overwhelming, particularly for small organizations. It may even make us question our understanding of how museums should operate. However, small, concrete actions will help shift museum and public practices and values to ones that help future community enrichment.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed